Ireland’s tax haven model hangs in the balance as Trump’s administration threatens to end it. This would be a substantial blow to the Irish state’s revenue and private sector’s well-being. In addition, the macro-effects of an American-EU trade war could diminish any remaining value that Ireland provides as an economic bridge between the two. In his most recent speech, Trump announced tariffs on pharmaceuticals and singled out Ireland as a prime target to penalize. Dan O’Brien, chief economist at the Institute of International and European Affairs, wrote the launch of this trade war could shape up “to be worst day in Irish economic history since September 29 2008 and December 2010…longer run impact on Ireland’s economic model could well be more profound than 2008/10.”

In light of this, Ireland should think deeply about how to move forward. While there are many policies that could be beneficial and many esoteric wonkisms on the margins to be done, here are three big policy ideas that I believe would get the most bang for the buck.

1.) Expand Bank Credit

Ireland’s over-reliance on foreign investment is premised on the assumption that “there is not enough money in Ireland.” Thus, Ireland must make itself dependent on others instead of “ourselves alone.” Is this true?

Turns out, it’s not. There’s plenty of money in Ireland. The way to evaluate that is to look at Ireland’s bank credit to deposit ratio. This ratio basically says for every dollar of loans issued how many dollars of savings is backing it up. Generally, we might consider it safe to have a lot of savings backing up loans in case anything goes awry. But Ireland has the opposite problem: it’s starved of credit relative to its savings.

Ireland’s bank credit to bank deposit ratio was 38 percent as of 2021. The ratio declined by 77 percent from its 2008 high of 167 percent. While some diminishment might be expected from that period, it has severely gone below an appropriate level. From 1972, the ratio declined by 52 percent. From 1960, the ratio declined by 38 percent. How is it possible that present-day Ireland requires substantially less credit relative to deposits than 50 to 60 years ago? This is absurd on its face. Ireland’s 2021 bank credit to bank deposit ratio was 57 percent below the European average.

For example, it was 57 percent lower than Germany’s, 59 percent lower than the Netherlands’, 65 percent lower than France’s, 75 percent lower than Sweden’s, 78 percent lower than Norway’s, and 86 percent lower than Denmark’s. Ireland has the second lowest recorded ratio in Europe. Finally, Ireland’s ratio is 32 percent lower than the global average, and is, in fact, one of the lowest recorded in the world. Angola followed by Zambia sat lower than Ireland followed by Ghana then Sudan which sat higher.

This is ridiculous. The obvious source of Ireland’s stifled domestic economy and even its housing crisis, is the unwillingness of private banks to sufficiently lend to Irish people. There are three reasons for this. One, Irish banks are shell shocked from the early 2000s housing bubble and over-correct by not lending enough. Two, Irish banks have historically underlent to Ireland’s domestic economy due to legacies of imperial underdevelopment and Anglo-centric economic ideas to justify it. Three, the Irish state has always shied away from confronting the banking interests of Ireland out of fear of economic collapse and insecurity in overstepping their perceived “betters” (often those of Anglo-Irish Protestant stock who ran the banks).

The bottom-line is that Ireland needs to find a way to increase the lending of private Irish banks. There are limitations given Ireland’s subordinate status in the European Union and European Monetary Union, but it must pursue this. The most direct policy is central bank window guidance. This is a tool central banks use to establish lending quotas to different sectors of the economy.

On its efficacy, economist Maurice Starkey explained that window guidance was the “effective control and direction of credit by the monetary authorities supported rapid Japanese economic development during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Credit controls should be developed with the aim of achieving specific economic growth targets…[Although] it is not sufficient simply to have credit controls in place. Credit controls implemented by the monetary authorities must aim to avoid excessive credit creation by the banking system, and limit the amount of credit being directed towards the purchase of speculative assets.” Further information can be found in economist Richard Werner’s “New paradigm in macroeconomics: solving the riddle of Japanese macroeconomic performance” book which Starkey referenced.

Ireland should petition the European Central Bank to conduct window guidance in order to increase lending in Ireland. Although, Ireland returning monetary sovereignty to its own national central bank would be more efficient, there’s a larger political conflict that would be required to achieve such an outcome. With that being said, if Ireland pulls out of the European Monetary Union and is no longer under the control of the European Central Bank, the Irish state could better optimize its monetary policy to its own individual problems.

Another policy would be to copy the Italian mini-BOTs idea for Ireland. The original mini-BOT proposal by Claudio Borghi Aquilini can be read about here. Mini-BOTs were non-interest bearing Italian Treasury bills that could have been used as a money substitute. While never realized, the idea sought to evade those continental limitations to fix the specific problems of Italy which required a higher money supply because the mini-BOTs were not technically considered money and thus not skirting European Central Bank’s domain.

Increased capital controls would also be necessary to prevent capital flight from both anxious animal spirited investors and piratical foreign speculators. An increased money supply through mini-BOT-like instruments in Ireland could directly invest in needed sectors, like housing, and stimulate Irish banks to lend more due to fractional reserve money multiplier theory. Other policies could include tax credits, loan guarantees, and creating a national bank to compete with private banks in the private sector to spur activity.

2.) Invest in Manufacturing

Ireland is not an industrial country in the same way others are. Most industrial countries got that way through a large manufacturing base rather than over-relying on services as Ireland does. Some might say Ireland’s small size prevents it from doing so, but manufacturing-centric small countries like South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Switzerland, and others refute that claim.

In fact, the much lauded Celtic Tiger success was the result of manufacturing-centric policy. Charles Haughey initiated this style of state-led industrial policy that lasted through the 1980s and 1990s. In a 1996 report prepared for the European Commission, researchers from University College Dublin and The Economic and Social Research Institute validated the policies and revealed stellar Irish performance relative to peers.

Between 1988 and 1995, employment in indigenous Irish firms increased by 3% more than in most EU countries, whose industrial employment declined on average over the same period.

By 1992, 35.6% of indigenous Irish industry output was exported, which was up from 26.6% in 1986. The value of indigenous manufacturing exports, in dollar terms, increased by an average of 16.9% per year in the period of 1986-1992, compared with an average annual increase of 11% for the manufacturing exports of the EU.

Total Irish manufacturing employment has shown relatively strong growth, with an increase of 14% in the period 1987-1995, compared with an overall decline for the EU.

The success of manufacturing-centric policies occurred with other contingent requirements. Domestic firms had to be emphasized over foreign ones. The manufacturing activity had to be of sufficiently high skill levels and produce globally rare goods. Those goods needed to be exported to foreign markets rather than just the internal one. As Michael Taft — an economic researcher for the Services Industrial Professional and Technical Union (SIPTU) — wrote, “they targeted multinational corporations (MNCs) in very specific, high value-added areas (electronics, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, software, etc.)...This wasn’t a self-selection process — it was a deliberate targeting of sectors.”

Low skill manufacturing of commoditized goods leads to diminishing returns eventually. The only way to truly grow and profit is to continually move up the manufacturing value ladder. Today, one sector of particular importance is semiconductors. Ireland already has a significant industrial base thanks to Intel. This makes Ireland the second largest exporter of semiconductors in Europe (right behind Germany). It is also helped by China being a great buyer which makes up about 40 percent of Irish semiconductor exports. The rest of Asia makes up another 30 percent meaning 70 percent of Irish semiconductor exports go to Asia rather than Europe or America.

With this impressive base to start from, Ireland should double down and invest more in this industry. It should direct its increased bank credit into it. It should find ways to improve infrastructure to assist in its growth. It should conduct more diplomacy with Asia to foster even more trade. Taiwan is a small island nation too, but it makes up 68 percent of the global semiconductor market. There’s no reason why Ireland can’t replicate that in some fashion. For critics that might scoff at Ireland’s capabilities to venture into such a trajectory, many mainstream western economists also criticized South Korea’s attempt to transform into an industrial player in the 1970s. In 1973, Korea officially launched its industrial strategy with shipbuilding as a primary sector. In about ten years, South Korea had a larger market size than all of Europe in shipbuilding. There’s a lesson there.

3.) Unleash Fossil Fuels

Any manufacturing growth will have to be driven by an expansion of fossil fuels. There’s no getting around this reality. The International Energy Agency (IEA) affirmed that heavy industrial processes require a large degree of fossil fuels because of inherent needs to generate heat, provide raw material inputs, sustain chemical reactions, and drive mechanical equipment. It’s effectively impossible to replicate this system with the substitution of renewable alternatives at any reasonable scale.

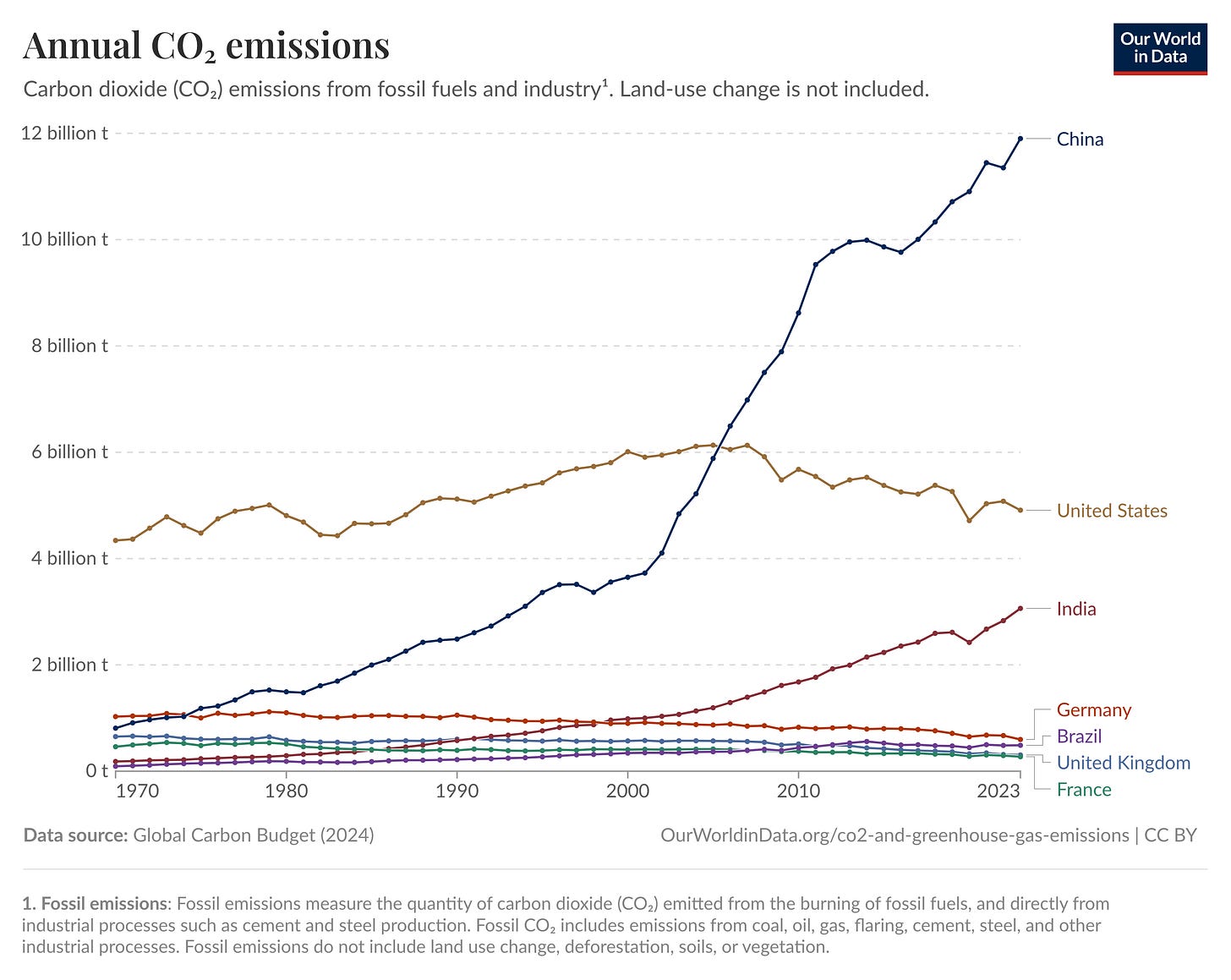

China rapidly developed its economy by embracing fossil fuels. They are the number one carbon emitter in the world today. Every other developed country, especially in the west, followed the same path although slightly earlier. This is not a bad thing. China lifted the most amount of people ever out of poverty doing this strategy. Today, they must sustain their increased living standards for over a billion people and role as a manufacturing exporter to the world by continuing to rely on fossil fuels and eschewing western-centric constraints on its carbon emissions.

China is a leader in green technologies but only because it has a reliable and large base of fossil fuels to depend on and fuel the manufacturing of all that green technology in the first place. If Ireland wants to be a real leader in green technology, particularly in wind given its celebrated windy Atlantic coastline, it should build its own wind turbines rather than buying them from other countries. Especially since there is no reason that green investment should not go to Irish companies and Irish employees. In order to facilitate that wind future, fossil fuels are a requirement. As Vaclav Smil, Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Manitoba, explained in his IEEE Spectrum article:

Wind turbines are the most visible symbols of the quest for renewable electricity generation. And yet, although they exploit the wind, which is as free and as green as energy can be, the machines themselves are pure embodiments of fossil fuels.

Large trucks bring steel and other raw materials to the site, earth-moving equipment beats a path to otherwise inaccessible high ground, large cranes erect the structures, and all these machines burn diesel fuel. So do the freight trains and cargo ships that convey the materials needed for the production of cement, steel, and plastics. For a 5-megawatt turbine, the steel alone averages…150 metric tons for the reinforced concrete foundations, 250 metric tons for the rotor hubs and nacelles (which house the gearbox and generator), and 500 metric tons for the towers.

…

A 5-MW turbine has three roughly 60-meter-long airfoils, each weighing about 15 metric tons. They have light balsa or foam cores and outer laminations made mostly from glass-fiber-reinforced epoxy or polyester resins. The glass is made by melting silicon dioxide and other mineral oxides in furnaces fired by natural gas. The resins begin with ethylene derived from light hydrocarbons, most commonly the products of naphtha cracking, liquefied petroleum gas, or the ethane in natural gas.

…

Undoubtedly, a well-sited and well-built wind turbine would generate as much energy as it embodies in less than a year. However, all of it will be in the form of intermittent electricity—while its production, installation, and maintenance remain critically dependent on specific fossil energies. Moreover, for most of these energies—coke for iron-ore smelting, coal and petroleum coke to fuel cement kilns, naphtha and natural gas as feedstock and fuel for the synthesis of plastics and the making of fiberglass, diesel fuel for ships, trucks, and construction machinery, lubricants for gearboxes—we have no nonfossil substitutes that would be readily available on the requisite large commercial scales.For a long time to come…modern civilization will remain fundamentally dependent on fossil fuels.

The path to expanding, using, and championing green technologies is through fossil fuels. Perhaps, only when enough momentum is gained from fossil fuel utilization can society reach an inflection point to diminish them in favor of alternatives — like a rocket ship discarding its booster rockets. All those green technologies, as well as nuclear, take years and large volumes of fossil fuels to get to a significant threshold. Ironically, in order to go green, Ireland first must embrace the black stuff. And Ireland doesn’t have to go far to do so. With the efficacy of green technologies (excluding nuclear) is still in question, the only way to justify experimentation with it is by having a large reliable base of fossil fuels.

Ireland traditionally sourced all of its natural gas from its offshore fields like Kinsale Head and Corrib. In 2021, Ireland banned all new oil and gas exploration and drilling citing its concern for climate change. As the existing national supply gets depleted it is estimated that by 2030 Ireland will be over 90% reliant on the United Kingdom for natural gas imports and eventually 100%.

Ironically, Ireland’s increased dependence on UK-sourced natural gas has put pressure on the UK to expand its offshore exploration and production. The ban, led by the Green Party’s Eamon Ryan, didn’t actually do anything to stop the extraction of natural gas, it just shifted it to the UK. Similarly, almost all of Ireland’s petroleum consumption comes from imports, especially from the UK.

The most tangible prospect for new Irish extraction is the Barryroe field. Barryroe is 50 km off the south coast of Ireland at about 100 meters in depth. It has been considered one of the largest undeveloped oil and gas discoveries in Europe. Notably, it is Ireland’s first commercial oil discovery too. The Barryroe field is estimated to contain 300 million barrels of oil and 5.9 billion cubic meters of gas. With further development and drilling deeper, there’s an optimistic case that there could be anywhere from 2-3x recoverable reserves.

To put this in perspective, Ireland consumes about 50 million barrels of oil per year and 5.2 billion cubic meters of gas. The current reserves of the North Sea field, where the UK sources its oil and gas of which Ireland imports from, consists of about 4.4 billion barrels of oil. It was suggested that a market price of $55 per barrel of oil would be needed to make the project profitable which would make the total value of the field $16 billion. That means just this one project would be approximate to the annual tax revenue received from corporations in Ireland or about 6% of modified GNI.

Barryroe is the most accessible and newsworthy project but there’s much more. Many may not realize this but Ireland is far bigger than one assumes, at least when you include its territorial waters. Ireland’s total size is 10x its landmass. All of this territory, especially the underwater basins, is available to be explored.

Excluding the Celtic Sea area that includes the Barryroe field, just the Atlantic area is estimated to contain the potential equivalent of about 10 billion barrels of oil, according to an Irish government report. The 10 billion is split between 6.5 billion actual barrels of oil and 20 trillion cubic feet of natural gas or 566 billion cubic meters.

This would provide Ireland with 130 years of 100% Irish sourced oil and 108 years of 100% Irish sourced gas. The total value of the Atlantic fields is estimated at about $700 billion to $1 trillion.

This would place Ireland in the top 20 countries by oil reserves. It would be in the same league as countries like Norway but most notably it would place Ireland above the UK (US EIA).

These positive signs are compounded by the fact that Europe is desperately seeking replacement of Russia as a source. Why couldn’t Ireland, as a good European neighbor, fill in that role? Norway increased its exports greatly during the crisis but has a ceiling. 50 percent of total Norwegian exports are now fossil fuels. If it’s alright for Norway to expand, why not Ireland? Ireland could be a champion of European cohesion by stepping up as a major trading partner in oil and gas.

Thus, reintroducing fossil fuel production and consumption into Ireland accomplishes a variety of goals. It provides needed energy to expand industrial manufacturing. It provides a resource to export into a European market with a shortage of supply. Lastly, it secures the Irish nation with a cheap and reliable supply of domestically produced energy that is not at the whims of foreign countries.

Conclusion:

This essay has compiled three big policy ideas to fix Ireland’s economy. First, the expansion of bank credit is posited as a critical lever for mitigating Ireland’s housing crisis and stabilizing the precarious private sector by enhancing liquidity and stimulating investment. Second, a renewed emphasis on manufacturing is identified as a foundational driver of economic growth, offering not only stable employment but also positive spillover effects across secondary sectors. Finally, the strategic development of domestic fossil fuel resources is proposed to secure essential industrial inputs, bolster export capacity, lower consumer energy costs, and enhance national security. While numerous other policy interventions merit consideration, these three proposals are presented as the most impactful in addressing Ireland’s economic imperatives.

For more information on each idea, please read my longer essays below:

Irish Banks Are Starving Ireland’s Economy

In 1922, Michael Collins wrote “Business cannot succeed without capital. Millions of Irish money are lying idle in banks.” He referred to the fact that while honest and hard-working Irish people responsibly accumulated savings, the Irish banks neglected their duty to finance domestic Irish business at an appropriate level justified by the savings availa…

The Rise and Fall of the Celtic Tiger

What was the Celtic Tiger? It was a period of economic development and growth in the 1990s that had an impact on Irish society that reverberates to this day. As a country that has dealt with extreme poverty pre-20th century and moderate poverty in the 20th century, the Celtic Tiger was a stark anomaly in rapidly improving key economic performance indica…

Drill Boyo Drill: The Case for Ireland's Oil and Gas Potential

Ireland pays the highest electricity bills in all of Europe, and the country’s diesel and petrol prices are also rising.

This moment has been mooted since Obamas first run, but you can guess our comprador supine ruling class has no plan.