Ireland pays the highest electricity bills in all of Europe, and the country’s diesel and petrol prices are also rising.

Ireland has suffered some of the worst consequences of the global energy crisis caused by the disruption of Russian energy exports due to the Ukrainian conflict. This is compounded by the developing world’s rapidly increasing global demand for energy. Ireland is faced with a situation of dwindling available supply and expanding competition for that supply.

Energy is everything. It’s the basic input that keeps society running. You don’t fool around with it. Ireland could ensure its national security needs and even expand its commercial horizons by drilling for oil and gas in its offshore territorial waters.

What do you mean oil and gas? There’s none of that here! And it would increase climate change! Take a deep breath. This might seem laughable or impossible to some – but this conversation needs to happen. The bottom line is that Ireland needs energy, and the much-promoted wind solution will not cut it. We need to look at fossil fuel.

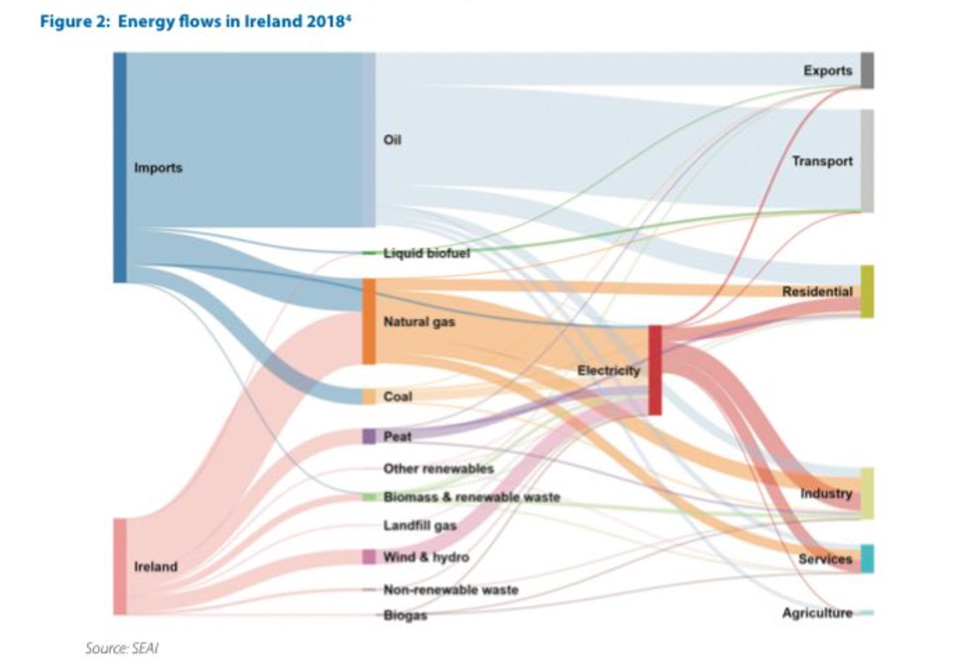

According to Electricity Maps, as of the time of writing, wind energy contributed 12% to Irish electricity consumption with natural gas making up 66% of the total. Wind can fluctuate for a better contribution but this source is ultimately reliant on natural gas plants to bail them out when the wind stops blowing.

Ireland doubled its installed wind capacity in the past decade and yet Ireland still experienced terrible effects of the energy crisis.

Wind is interesting but only so in a fully secure and diverse energy sector. The total reliance on wind is an incredible vulnerability. There is no getting around that for abundant wind energy to be successful it must have abundant natural gas backing it up. Wind also has no bearing on the vast majority of vehicles that continue to use petrol and diesel.

INCREASED DEMAND

Overall demand for electricity, transportation, and heating will only increase in the future as well. According to EirGrid, “the energy demand is forecasted to increase 37% by 2031.” By myopically focusing exclusively on renewable energy, Ireland risks a major self-induced crisis.

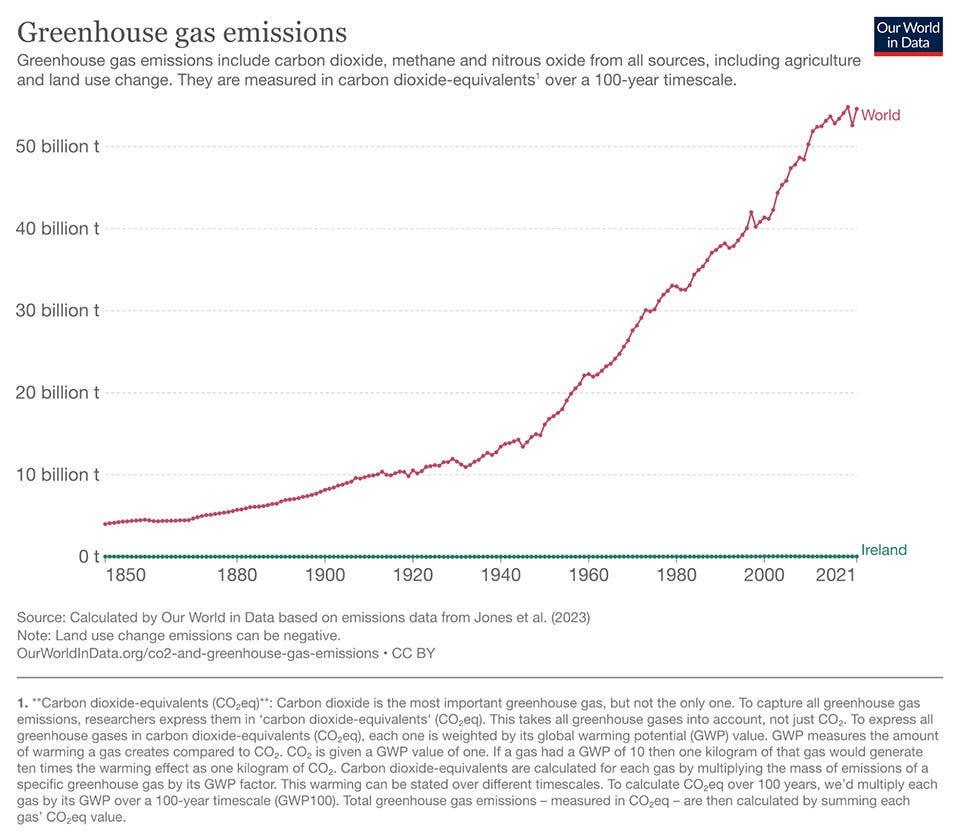

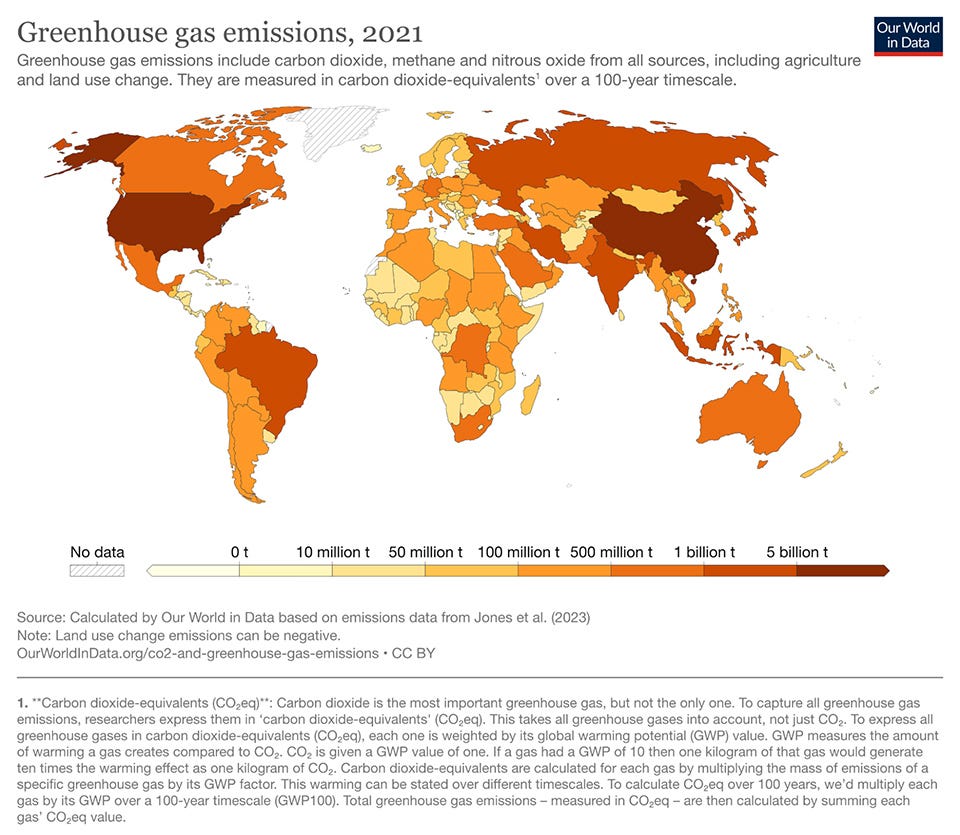

But won’t more fossil fuels increase carbon emissions? Yes. Let’s contextualize this. Ireland’s 2021 greenhouse gas emissions were 58 million tonnes. Ireland’s share of global greenhouse gas emissions was 0.1%. The world needs to cut about 30 billion tonnes by 2030 and 48 billion tonnes by 2050 to have any meaningful chance of stopping climate change. Let me repeat this. Ireland’s share of global greenhouse gas emissions was 0.1%. Frankly, Ireland does not matter. Climate change won’t be materially impacted whether Ireland emitted zero greenhouse gas emissions or doubled it.

For those who believe emissions must be lowered to avoid a climate emergency, Ireland is not the country of concern. China, America, India, Russia, Brazil, Indonesia, Japan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico make up the top 10 greenhouse gas emitters for a share of 62% – while some rapidly developing countries are exponentially increasing their emissions like Pakistan and Turkey. This should be rather obvious but for those feeling the need to bring up Ireland’s per capita emissions, climate change doesn’t care about per capita it only cares about aggregates.

We’ve established that Ireland is in an energy crisis, wind energy cannot be relied upon, fossil fuels continue globally to be a huge part of energy consumption, and Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions are irrelevant to global trends.

Now, let’s turn to Ireland’s oil and gas sector.

OFFSHORE FIELDS

Ireland traditionally sourced all of its natural gas from its offshore fields like Kinsale Head and Corrib. In 2021, Ireland banned all new oil and gas exploration and drilling citing its concern for climate change. As the existing national supply gets depleted it is estimated that by 2030 Ireland will be over 90% reliant on the United Kingdom for natural gas imports and eventually 100%.

Ironically, Ireland’s increased dependence on UK-sourced natural gas has put pressure on the UK to expand its offshore exploration and production. The ban, led by the Green Party’s Eamon Ryan, didn’t actually do anything to stop the extraction of natural gas, it just shifted it to the UK. Similarly, almost all of Ireland’s petroleum consumption comes from imports, especially directly from the UK and indirectly passing through the UK like formerly Russian oil.

There is no effect on climate change by shifting natural gas extraction from Ireland to the UK – however, there are negative effects for Ireland.

Ireland will be beholden to the UK decision making which would be compromised in another energy shortage leaving Ireland last in line. Irish companies also miss out on the revenue generated from the industry. Those Irish companies would have employed Irish workers too. The Irish government ceded regulatory control of the sector to the UK.

In short, a deal that provides no benefits but all costs is an incredibly stupid deal.

The most tangible prospect for Irish extraction is the Barryroe field. Barryroe is 50 km off the south coast of Ireland at about 100 meters in depth. It has been considered one of the largest undeveloped oil and gas discoveries in Europe. Notably, it is Ireland’s first commercial oil discovery too.

300 MILLION BARRELS OF OIL

The Barryroe field is estimated to contain 300 million barrels of oil and 5.9 billion cubic meters of gas. With further development and drilling deeper, there’s an optimistic case that there could be anywhere from 2-3x recoverable reserves.

To put this in perspective, Ireland consumes about 50 million barrels of oil per year and 5.2 billion cubic meters of gas. The current reserves of the North Sea field, where the UK sources its oil and gas of which Ireland imports from, consists of about 4.4 billion barrels of oil.

It was suggested that a market price of $55 per barrel of oil would be needed to make the project profitable which would make the total value of the field $16 billion.

That means just this one project would be approximate to the annual tax revenue received from corporations in Ireland or about 6% of modified GNI.

However, the past 5 years have seen the price of oil notably above that. It reached highs of $120 and now rests at $80. The revised numbers would be a total value of $24 billion at 10% of modified GNI.

It must be noted that this is also the conservative assessment of one aspect of the circumscribed area, which means with further development it could be much more valuable.

Following the 2021 ban, Barryroe was grandfathered in and allowed to continue given its earlier work. However, the final nail in the coffin of the private development of this field was allegedly an illegitimate regulatory veto on further operations by Eamon Ryan.

Many have cited Ryan’s extreme green ideology as the cause rather than any valid concerns of the financial viability of the project. The interests behind Ballyroe are now considering suing the government.

As the Currency’s Sean Keyes wrote, “the big bottleneck is not geological, it’s not economic, it’s political.” In general, the expansion of the oil and gas industry in Ireland has never really been about the viability of its fields but about the ideological temperament of the government and fringe minority lobby groups.

Investors say “they are not going to touch Ireland” because of the hostile ideological environment that could break norms and laws to hurt the industry. In PWC’s 2019 report on the Irish oil and gas industry, survey respondents cited the main roadblocks facing the development of the industry was regulatory complexity and unfriendliness of the Irish government.

OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

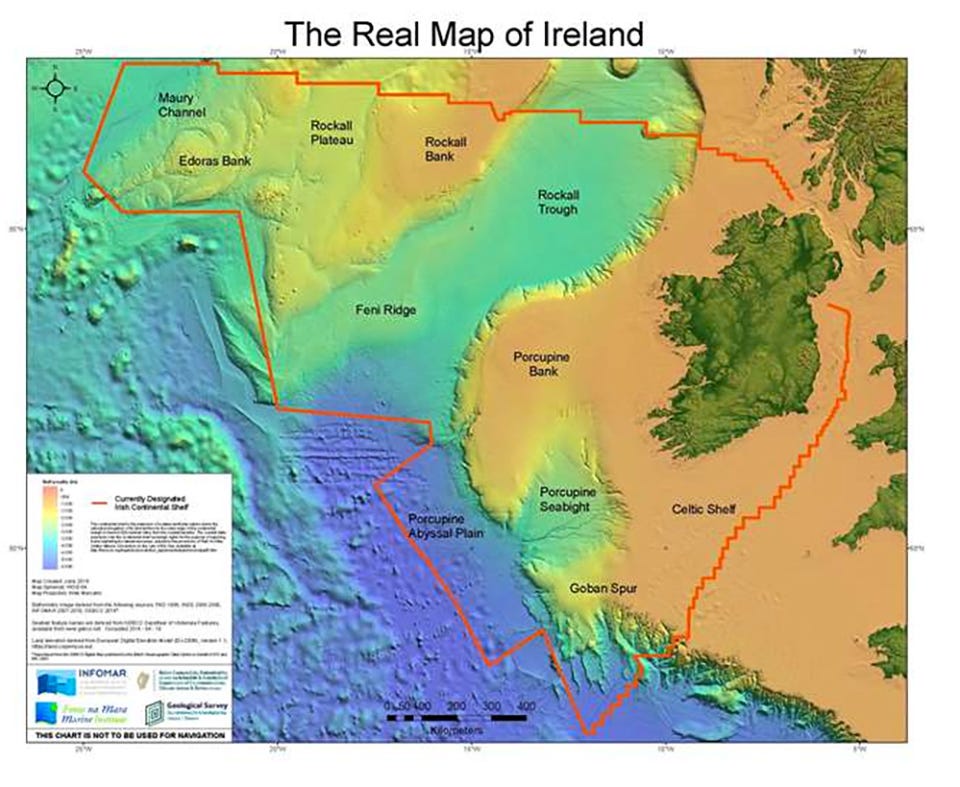

Ballyroe is the most accessible and newsworthy project but there’s much more. Many may not realize this but Ireland is far bigger than one assumes, at least when you include its territorial waters. Ireland’s total size is 10x its landmass. All of this territory, especially the underwater basins, is available to be explored.

Excluding the Celtic Sea area that includes the Ballyroe field, just the Atlantic area is estimated to contain the potential equivalent of about 10 billion barrels of oil, according to an Irish government report.

The 10 billion is split between 6.5 billion actual barrels of oil and 20 trillion cubic feet of natural gas or 566 billion cubic meters.

This would provide Ireland with 130 years of 100% Irish sourced oil and 108 years of 100% Irish sourced gas. The total value of the Atlantic fields is estimated at about $700 billion to $1 trillion.

This would place Ireland in the top 20 countries by oil reserves. It would be in the same league as countries like Norway but most notably it would place Ireland above UK (US EIA).

According to PWC’s Irish oil and gas industry report, oil prices need to be about $50-$70 per barrel for these projects to be commercially viable. Notably, survey respondents who considered commercial viability below $50 per barrel jumped from 5% to 23% from 2018 to 2019 indicating more confidence in accessibility.

Given that the current price hovers at $80 and could reach $120, the commercial viability of the Irish oil and gas industry seems very assured. According to energy research firm Wood Mackenzie, Ireland has a lower breakeven cost than the UK for deep sea drilling.

These positive signs are compounded by the fact that Europe is desperately seeking replacement of Russia as a source. Why couldn’t Ireland, as a good European neighbor, fill in that role?

Norway increased its exports greatly during the crisis but has a ceiling. If it’s alright for Norway to expand, why not Ireland? Ireland could be a champion of European cohesion by stepping up as a major trading partner in oil and gas.

One of the biggest challenges to the development of the Atlantic area has been its depth. Corrib is at a depth of 355 meters, Kinsale at a depth of 100 meters, and Ballyroe at a depth of 100 meters. Prospective reserves could be as deep as 400 to 3,000 meters.

In prior years with low oil prices, this depth challenge created the need for a higher price than market to be commercially viable.

However, improvements in seismic survey and deep-sea drilling technologies have increased. Today, more precise data can be more easily obtained on deposits and how much is recoverable.

IMPROVED TECHNOLOGY

According to Professor Steven A. Murawski and his colleagues, “in 2017, 52% of US oil production was from ultra-deep wells” defined as those exceeding 1,500 meters up from only 15% in the 2000s.

Wood Mackenzie wrote, global “deepwater production has grown from below [3,000 barrels of oil per day] in 1990, to 10.3 million [barrels of oil per day] in 2019.”

Improved deep sea drilling technology is also leveraged for other commodities besides oil and gas. There has been a significant push in deep sea mining for things like copper, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and more. Many of these are inputs for green tech like solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries.

Japan has just started mining in depths of 2,500 to 6,000 meters for these commodities.

All these examples show that technological change can make Irish offshore deep sea drilling for oil and gas commercially viable. They also show the potential for expansion past deposits of oil and gas and into other commodities.

EXAMPLE OF NORWAY

Besides the technical challenges described above, the Irish government’s neglect in securing these natural resources has been significant.

The gold standard of European offshore drilling is Norway. Their success has been built on the back of the Norwegian government taking a proactive approach. The largest company in the sector Equinor (formerly Statoil) was started by the Norwegian state in the 1970s and has retained majority state ownership.

Government investment into it and other projects has enabled the private market to follow on behind them. The Norwegian government also subsidizes losses for failed prospecting.

The incredible success of Norway’s energy sector has resulted in its much lauded sovereign wealth fund which is a repository for gains made from the selling of the energy. This multiplied the value of those energy revenues by investing those proceeds into the general Norwegian economy and abroad. They created a sounder and larger fiscal position for the country through smart utilization of their resources.

Ireland, on the other hand, failed to develop a substantial state-owned enterprise and outright dismantled any pursuit of such in the 1990s. The Irish state has had no equity or ownership in any project since then.

The Irish state has only copied and pasted its general low tax schemes in the sector. The United States receives more income percentage wise from its oil and gas sector than Ireland’s. While that might be a strong incentive for private development, it’s an incredibly inconsiderate approach that sells the Irish nation short of what it is properly due for its resources.

With more state involvement, Ireland could better capture the value of those offshore fields directly and apply that to other policies like emulating Norway’s sovereign wealth fund or building more housing.

Another consideration is that any private and/or foreign company that drills in Ireland has no obligation to sell that energy to the Irish. They could drill, package it, and ship it off to another country without it ever touching Irish land. No company is even required to sell at reduced prices to the Irish. In a future where the Irish state is more proactive, obligations could be placed on these companies to sell to Ireland first and at discounted prices.

WE’RE NOT UTILIZING POTENTIAL

Critics will often argue that Norway can pursue its oil and gas industry because it is predicated on its 1 in 5 success rate of commercially viable drilled projects. The critics then contrast this to Ireland’s dismal 1 in 25 success rate. But after considering everything this essay has stated thus far, we can see there are problems with taking that as gospel.

To start, Ireland has drilled a total of 160 wells while the UK has drilled 4,000 wells. Ireland is only 3.5 times smaller than the UK so a comparable ratio would be about 1,100 drilled wells. The sample size to evaluate Ireland’s true offshore oil and gas potential is obviously too small to make any grand sweeping conclusions.

This small number of drilled wells is symptomatic of the Irish government’s neglect to properly lead the way on initiating projects through subsidies and state-owned-enterprises. They also have failed to consider the advancement of deep sea drilling technology in the past 20 years which drastically changed the economics and operational capacity of Ireland’s Atlantic territorial waters.

The combination of this technology with a proactive and friendly state could certainly change perception of potential success.

IRELAND’S ECONOMIC SECURITY

Ireland has the potential to tap almost $1 trillion in its deep sea Atlantic waters and possibly much more when including other regions like the Celtic Sea where the Ballyroe sits as well as novel underwater mining for other commodities. The Ballyroe project would be the most accessible one to begin production on and bring tangible benefits to the Irish people as well as probable export opportunities when supply overshoots demand.

Embracing Ireland’s national resources would create jobs, stimulate foreign direct investment, increase spending in the Irish economy, and increase tax revenues to the government. It would also provide ample energy needed to expand Ireland’s industrial sector. For example, Intel wants to double its semiconductor business in Ireland by 2030.

It would also increase Ireland’s national security and reduce dependence on foreign countries that could unilaterally destabilize Irish energy imports. In another energy crisis, Ireland would have no recourse in guaranteeing its energy when the countries it sources from are rationing energy at home, leaving Ireland last in line if in line at all.

Henry Farrell is the SNF Agora professor at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, 2019 winner of the Friedrich Schiedel Prize for Politics and Technology, and former editor-in-chief of the Monkey Cage at the Washington Post.

He just published “Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy” and wrote a recent op-ed about it and the context of Ireland in The Irish Times.

In it he wrote,

“instead of bringing peace, globalised networks have often increased insecurity. This will worsen as great powers exploit each others’ vulnerabilities, and retaliate against each other for this exploitation. The global economy isn’t set to collapse, but it can’t be treated in isolation from national security any more. Ireland needs to start thinking through the consequences…Ireland needs to focus more on economic security, where its main vulnerabilities lie.”

In the face of an energy crisis where Irish people are paying high prices and risk blackouts caused by an energy supply built on globalised networks, Ireland should take Farrell’s advice and seek national solutions. Ireland should embrace national sources of energy starting with oil and gas in its offshore waters.

The Irish government should invest in the facilitation of exploration and production, take more ownership of the projects, and mandate quantities of energy at discounted prices for the Irish people. Private companies should be allowed to safely and sustainably explore and drill in Ireland’s offshore waters with proper oversight by the state but with the support necessary to push the industry forward.

Ireland could be the largest energy producer in Europe and even vie for the top 20 of the world in the future. The only thing holding Ireland back is not economics, geology, or technology but the lack of will.

Before he died, Michael Collins wrote,

“the keynote to the economic revival must be development of Irish resources by Irish capital for the benefit of the Irish consumer…How are we to develop Irish resources?..Conditions must be created which will make it possible for new ones to arise…our mineral resources must be exploited.”

Collins’ vision was partly achieved in the completion of the Ardnacrusha hydroelectric power plant on the Shannon River which was similarly criticized as unrealistic at first but went on to power almost 100% of Ireland’s electricity needs for years to come.

The Financial Times, upon the completion of the plant, wrote that the Irish were “the shrewdest of psychologists. They have thrown on their shoulders no easy task of breaking what is in reality an enormous inferiority complex, and the Shannon Scheme is one—and probably the most vital—of their methods of doing it.”

In the spirit of Collins’ vision, Ireland, today, can reject inferiority and ascend to great heights. If it only has the will to do so.

This article was originally published on Gript on September 6, 2023.