What Ireland's Mainstream Narrative Gets Wrong About Irish Economic History

Debunking the Black Sheep Myth of Irish Protectionism

The mainstream narrative of Irish economic history poorly explains reality yet is leveraged to justify present policies. The narrative coveys a simple before and after story of two sides, but the reality is far more nuanced. The ultimate aim of the narrative is to delegitimize protectionism in favor of free trade liberalism. It is said that protectionism is the black sheep of Irish economic history but once the true history is fully understood, the logical conclusion is the opposite.

The mainstream narrative goes like this. Irish revolutionaries of the 1916 generation are conceded to have had idealistic economic wishes but ultimately those were built on impractical protectionist policies. Those ideals were sourced from a Napoleon complex of Irish parochial nationalists who wanted Ireland to perform like the big nations which was divorced from any careful economic study. Once independent, the new Irish state gave those ideas a fair play but it was a failure. So in 1958 with T.K. Whitaker's paradigmatic economic report and recommendations, Ireland pivoted to free trade liberalism and its economy took off ever since. The problem is that this narrative crumbles the minute someone opens a book.

The deep historical roots of protectionism in Ireland go back to the 1600s. Britain imposed artificial economic constraints on Ireland that disturbed the natural industrial development in Ireland. Ireland wanted to protect its own infant industries from the dominant British competitors in order to mature them and expand the Irish economy. They also wanted to export those industrial goods to other countries besides Britain. Ireland was prohibited of both desires by Britain. “They realised that their infant manufacturers could never permanently establish themselves as long as British merchants with large capitals and extensive trade connections were able to pour their goods into the country while secure in their own markets from all Irish rivalry.”1 Irish dissatisfaction was so tangible that there were riots over it which needed to be put down by the military. This cause was one of the primary motivations that fed into the zeitgeist that culminated in the Irish Rebellion of 1798. After its defeat, the Act of Union cemented those constraints and prohibitions of protectionism in Ireland which aggrieved Irish nationalist thought ever since.

The mainstream narrative is also at odds with any scholarly study done of Ireland’s historical economic relationship with Britain which legitimized protectionism. For centuries, various scholars took to the task and validated protectionists claims. Many of these writers came from non-nationalist and non-Irish backgrounds as well which not only removes their bias but makes their work even more efficacious given they were arguing against their own societal interest. The data was on the protectionist side.

For example, of the earliest, Provost of Trinity College John Hely Hutchinson wrote The Commercial Restraints of Ireland in 1779. He wrote, “national vigour and industry impaired by the law made in England restraining, in fact prohibiting…Ireland...commercial restraints and prohibitions give the British trader and manufacturer many great and important advantages over the Irish.” Of the tailend, Dr Alice Effie Murray (the first woman to receive a D.Sc. Econ. degree from the London School of Economics) wrote A History of the Commercial and Financial Relations Between England and Ireland in 1903. She wrote, “The industrial history of Ireland during the nineteenth century shows how impossible it was for Irish manufacturers to compete with British once the two countries were commercially united, and all custom duties on articles going from one country to the other gradually abolished. It also shows the advisability of a country possessed of little industrial development fostering and protecting its infant manufacturers until they are firmly established in order to prevent them being crushed out of existence by the competition of other countries. But union with Great Britain necessitated the application of the new free trade principles to Ireland just at the time when Irish industries should have met with encouragement and protection.”

Both partisan Irish nationalist literature and academic non-Irish literature produced arguments and data that legitimized protectionism throughout the long 19th century. This mountain of literature culminated in the Irish revolutionary generation of 1916 to 1922. Prominent nationalist Arthur Griffith detailed the exact economic doctrine in alignment with the past literature and younger leaders like Michael Collins were heir disciples to that doctrine. These two men became the most important official leaders of the victorious Irish Free State in 1922 and died in that same year. It is with their deaths that protectionism, as nationalists and academics knew it since Hely Hutchinson’s days, was abandoned.

The mainstream narrative’s simplistic binary of a naive revolutionary first generation which gave way in 1958 to an academic cosmopolitan second generation is just wrong. After Griffith’s and Collins’ deaths, the Irish Free State’s primary concern was the Irish Civil War and not letting the new state fall apart. With no leaders of sufficient economic vision as Griffith and Collins and in fear of economic collapse which other European countries experienced in that era, Cumann na nGaedheal quietly rejected protectionism. In this context, Cumann na nGaedheal relied on the economic status quo and the policy of not rocking the boat. The economic non-visionaries they turned to in Griffith and Collins stead were the pro-unionist economic establishment of Ireland.

TD Sean Milroy explicitly criticized the new state’s departure from the doctrines of Griffith and the return of free trade liberalism in 1924 and 19262. In his criticisms, Milroy leveraged historical and global evidence contrasting the naive and parochial slander the mainstream narrative labels pro-protectionists. Milroy wrote “I wish to suggest that [the state’s] direction is not satisfactory, not one that makes either for national health or economic stability, but one fraught with serious danger to the future of the State.” It is quite crude and uninformed to conflate the Cumann na nGaedheal government with protectionism.

This leaves the high ground of the mainstream narrative of Eamon de Valera’s government. While the forms of protectionism were there, the substance was severely lacking. De Valera's protectionism was divorced from the historical orthodoxy of Irish protectionist thought. For example, one the most egregious failures to live up to protectionist orthodoxy was the inability to establish a sovereign system of money and banking with a functional central bank and national currency. Overall, de Valera’s protectionism was haphazard and ill-thought. Some aspects of it weren’t economic at all but political reaction to fence with Britain in the Economic War. Other aspects were more so a poor application than a poor theory. For example, British firms with pass-through Irish domiciled firms were circumventing protectionist policies to keep them out and grow real Irish competitors.

TD Joseph Connolly, an insider to de Valera’s 1930s government, concluded in his 1953 memoir3 that “it is no mere captious criticism to complain that both in our whole conception of industrialisation and in giving scope for development there has been neither the care nor the imagination that we were entitled to expect…I could not help reflecting on how far we had deviated from all the plans, hopes and aspirations that had fired our minds some thirty or forty years ago.” Contemporary Irish historian Mary E. Daly corroborated that, after futile attempts at forms of protectionism, 1938 “marked the end of Fianna Fail economic radicalism…There is little doubt that the unduly ambitious aims of Fianna Fail and of earlier generations of nationalists were not met.”4 It is another oversight for the mainstream narrative to conflate de Valera’s poorly applied protectionism with orthodox protectionism. It would be like saying a chicken fillet roll that is missing the chicken is a perfect example of a chicken fillet roll. It’s not. It’s missing the most important ingredient. You don’t get points for the bread.

Finally, the second generation of free trade liberals are claimed to have ushered in unique ideas from global rather than parochial sources and that those globally-minded free trade liberal ideas were primarily responsible for Ireland’s modern economic high growth.

One such component of this claim is that the the second generation were unique in their desires to trade with the world opposed to the isolationist first generation. This could not be further from the truth. In 1924, Milroy also said, “Protection does not mean the exclusion of foreign competition. It means rendering the native manufacturer equal to meeting foreign competition.” In 1922 Michael Collins stated, “Foreign trade must be stimulated by making facilities for the transport and marketing of Irish goods abroad and foreign goods in Ireland.”5 In 1904 Griffith advocated that “Irish Consular representatives would…lead to the opening up of profitable and extensive markets for the Irish producer…[in] Argentina and Chili in South America, the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa, France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Spain, Russia, Japan, Denmark, Italy, and Austro-Hungary.”6 It is an outright falsehood to claim that Irish protectionists wanted zero foreign trade for Ireland. It is simply a straw man used by disingenuous or uninquisitive free trade liberals. The latter do not have a unique monopoly over foreign trade.

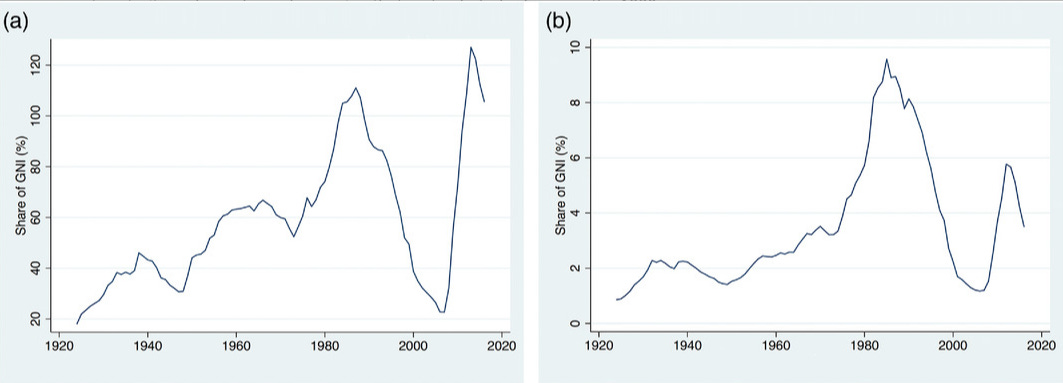

Next, the free trade liberal pivot, which began in the 1950s, failed to produce results until the late 1980s which is usually associated with the start of the Celtic Tiger high growth era. The pivot’s more direct result was the 1980 Irish debt crisis. This is because one of the key policy byproducts of the second generation free trade liberal zeitgeist was to raise foreign investment.

Irish economic historian Cormac Ó Gráda wrote, “Irish government debt had historically been low…Before the 1960s Irish fiscal policy had been cautious, arguably sometimes over-cautious…The oil crisis of 1973 prompted heavy borrowing abroad to support domestic demand, but the focus was on public current expenditure rather than capital spending. From the mid-1970s on, successive administrations sought to counter the impact of high oil prices and global recession by unsustainable deficit spending. A surging national debt generated by tax reductions and big increases in public expenditure—promises delivered by Fianna Fáil in the wake of their historical electoral landslide in June 1977—failed to generate the economic growth that would sustain it…So serious had the situation become by the mid-1980s that maverick economist Raymond Crotty counselled repudiation of the national debt, on the grounds that this would prevent future irresponsible governments from borrowing abroad.”7 While Ó Gráda laid the blame on a vulgar application of Keynesianism, his data is nonetheless agnostic and, as this author contends, could be more attributable to liberalizing attitudes on the expansion of foreign investment, especially foreign debt.

The Celtic Tiger’s true parent was the brief interlude of protectionism in the 1980s. One of its guiding economists was Erik S. Reinert who provided a modernized form of protectionism to Ireland. His 1980s report stated, “Successful indigenously-owned industry is, however, essential for a high-income economy. No country has successfully achieved high incomes without a strong base of indigenously-owned resource-based or manufacturing companies.”8 Maynooth University Professor of Sociology Seán Ó Riain reviewed the Celtic Tiger’s causes and found “the state was placed at center stage in industrial policy.”9 Rapid economic growth followed these policies in the 1990s. Unfortunately, the interlude gave way to a resurgence of free trade liberalism which atrophied Reinert’s industrial policy approach and led the way to Ireland’s greatest financial crisis in 2008. The irony of the mainstream narrative is that free trade liberalism was the culprit of Ireland’s greatest financial crises, not protectionism.

Lastly, the mainstream narrative completely ignores global literature on the state-led development school of thought which is an evolution of protectionism. The East Asian Tigers, from which Ireland's Celtic Tiger namesake is derived, achieved their high economic growth from very similar protectionist ideas that pre-1922 Irish nationalists were advocating. This global literature, that examines countries like the East Asian Tigers, comes from economists like Ha-Joon Chang. In his seminal book, Kicking Away the Ladder, he reviewed a wide variety of countries and time periods to conclude that protectionism, while never perfect, is the only path to economic development and all the currently rich countries took that path.

His book’s title is derived from a quote from 19th century economist Friedrich List, who Chang argued was one of the founders of protectionism and state-led development school of thought. The Atlantic’s James Fallows argued that the East Asian Tiger economic policies were greatly inspired by List. List was referenced by TD Milroy in his 1924 comments and constantly revered by Griffith in his economic tracts. Griffith wrote, “I am in Economics largely a follower of the man who thwarted England’s dream of the commercial conquest of the world…His name is a famous one in the outside world. His works are the text-books of economic science in other countries…I refer to Friedrich List, the real founder of the German Zollverein – the man whom England…hated and feared more than any man since Napoleon…the economic teacher of the nations…whose work on the National System of Political Economy I would wish to see in the hands of every Irishman.”10

Other modern state-led development writers include Alice Amsden, Robert Wade, and Mariana Mazzucato. The mainstream narrative has never attempted to approach scholarship from these sources and geographies. It is very much the case that the mainstream narrative is closed off to outside information and rather repeat mantras of its circular logic. Irish protectionism can now be seen as much more cosmopolitan in its appreciation for outside information and willingness to trade. It can be seen as much more academic in its extensive study of empirical data and history. Protectionism shouldn’t be the black sheep of Irish economic history. It is only fair to give past Irish nationalists their due in having a keener understanding of economics than most Irish free trade liberals do today. So long as many Irish people believe that protectionism is a black sheep, Irish free trade liberalism remains dominant and those who gain from it secure their interests.

It is best to conclude with a convergent summary of this nuanced position from historian Colum Kenny: “Griffith's collapse and death in August 1922 meant that he did not live to see the playing out of his aspirations for the economy of the independent Irish state on the world stage. And civil war pitched Ireland into economic self-harm, and into the kind of political division that Griffith–influenced by his memory of the Parnellite split– had always dreaded. Popular memory in Dublin has it that he died of a broken heart, and the memory of his death was an embarrassment to the survivors. He had been too socially and economically interventionist for Cumann na nGaedheal/Fine Gael…It has been said that in the 1920s, with some of the nationalist proponents of industrialisation such as Griffith dead, ‘better off farmers and professionals believed they would be worse off as a result of tariff policies’ and that when Fianna Fáil got into power ‘its advocacy of protectionism, unlike that of Griffith, was not directed towards the establishment of infant industries which would ultimately be expected to be competitive internationally.’ During the first decade of independence the new government did not in fact embrace protectionism, albeit the Irish state later adopted a form of it before developing a more open approach to commerce and trade. The latter would involve welcoming foreign direct investment, a free trade agreement with Britain in 1965 and membership of the EEC/EU in 1972. It should not be assumed that the later protectionist policies were those envisaged by Griffith, or that later enthusiasm for membership of the European Union is equivalent to earlier acceptance of the forms of free trade embraced by the United Kingdom when all of Ireland was a member of it.”11

Murray, Alice Effie. A History of the Commercial and Financial Relations Between England and Ireland: From the Period of the Restoration. United Kingdom, P.S. King, 1903.

Ryan, Peter. Irish Anti-Imperialist and Nationalist Economics. Ireland, University College Dublin, 2021.

Connolly, Joseph. How Does She Stand? An Appeal to Young Ireland. Ireland, Moynihan, 1953.

Daly, Mary E., Industrial Development and Irish National Identity, 1922-1939, Syracuse, 1992.

Collins, Michael. The Path to Freedom. Ireland, CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts, 1922 (1996)

Griffith, Arthur, The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland, Dublin, 1904.

Ó Gráda, C. and O'Rourke, K. H., ‘ The Irish economy during the century after partition’, Economic History Review, 75 (2022), pp. 336–70.

A Review of Industrial Policy. Telesis Consultancy Group, 1982

Ó Riain, Seán. The Flexible Developmental State: Globalization, Information Technology, and the" Celtic Tiger". Politics and Society. 28. 157–194, 2000

Griffith

Kenny, Colum. ‘A Man Who Has Both Arms’: Arthur Griffith, the Economy and the Anglo-Irish Treaty Agreement 1921. Irish Economic and Social History, 50(1), 74-92. 2022