South Korea's Fertility Crisis Explained

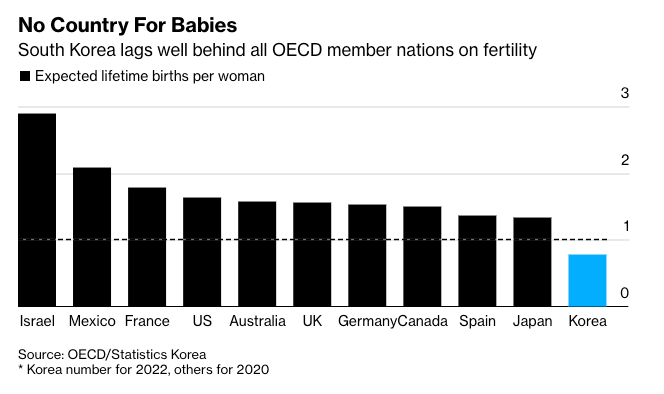

South Korea made headlines because of its startling low ranking in fertility. At .78 expected lifetime births per woman, South Korea is one of the lowest ranked among more than 260 nations tracked by the World Bank and the absolute lowest among the 38 members of the OECD. It has surpassed typical examples of low fertility like Germany and Japan. The standard for replacement level fertility is 2.1. While South Korea is mirroring similar trends across the developed world, what could be the reasons for its outlier status? Likely factors include economic hardship on the younger generation, increased female labour participation rate, and high urban concentration.

South Korean youth are disadvantaged because the older generation is distorting the economy by working later and wider while also having had a better initial rise in their youth. “South Korea’s legion of older workers has helped keep the jobless rate low but has exacerbated record low employment among the young - less than half of those aged 15 to 29 have jobs. It is also a cause of the decade-long stagnation in wage growth, dampening consumption.” Due to relatively low welfare programs in South Korea and cultural factors, South Korean elderly are uniquely more likely to work longer boxing out the youth from jobs that otherwise should go to them. The labour supply increase has also depressed wage growth. Additionally, the distribution of wealth in South Korea is skewed older and compounded by the higher growth rates experienced decades ago compared to lower growth rates today (9-10% growth in 1990s vs. 2-3% growth today).

South Korea has a higher female labour force participation rate than the OECD member average. The rapid rise of females in the workforce, as well as a shift to modern vs. traditional female economic activities, means that there are necessarily less females engaging in family formation. Additionally, this increase of females into the labour supply further pushes down wages just like the way older generations do.

Finally, South Korea has a very high central urban concentration. 20% of South Korea’s population lives in Seoul. Now compare this to 10% for Tokyo-Japan, 10% for London-UK, 10% for Dublin-Ireland, 2% Paris-France, and 4% Berlin-Germany. While there are nuances in distribution of urban centers contrasted to single urban centers, the highlight is South Korea has an abnormally high level of citizens in a densely populated city. Urban centers are generally population sinks. People have less room, more costs, more distractions, etc. Fertility will always be lower in cities.

In conclusion, South Korea’s fertility problem is caused by 1.) the older generation’s refusal to retire leading to increased labour competition and wage depression as well as wealth inequality from a faster growing economy in their youth 2.) an increase in female labour force participation rapidly leading to less females in the pool for family formation and an additional labour supply augmenting factor which depresses wages 3.) the very high centrality of the population in the main urban center which acts as a major drag of fertility. These factors are all compounded by a general lack of government supports whether it is for the elderly or child-rearing. The most impacted by these trends are South Korean young men who are either unemployed or underemployed which makes them less competent at family formation if their socioeconomic status is relatively similar to or lower than that their female counterparts.

A full stack economist should consider all these variables in economic policy. While crude changes like capping elderly and females in the work force might shift fertility, more elegant policies like increased welfare payments or debt reductions based on fertility-enhancing activities could do the trick while reaping the benefits from the modern trends. Additionally, building more medium cities or tech-enabled villages could reverse the urban sink effect. Culture is also an underlooked X factor. Policies in shaping attitudes around family and lifetime goals through media and education could rectify these issues too. The downside of letting your nation’s fertility crater is an unsustainable economic system where there aren’t enough workers increasing output, consuming, or paying taxes into the system.