In 2015, China opened the National Exhibition and Convention Center. It is the largest convention complex of its kind in the world. It hosts China’s International Import Expo which seeks to encourage foreign countries to export more to China. Most interestingly, the entire complex is in the shape of a four-leaf clover. Given the clover’s close association with Ireland, it seems like an auspicious sign of a future relationship between China and Ireland.

Irish economist Philip Pilkington frequently warns of the coming age of multipolarity. He suggests the rise of China represents a shift of economic centrality away from the U.S. Economic opportunities will come not from the traditionally dominant countries in the West but from emerging economies that have reached sufficient levels of development like China.

Pilkington wrote, “The major story that we see emerge is the rise of China, which has gone from around 3.2 percent of global trade in 2000 to around 12 percent of global trade in 2020. Remarkably China now makes up a larger share of global trade than the United States or the European Union…Recognizing this leads us to the conclusion that embracing connectivity should be a top priority of every nation in the world.”

Chinese Premier Li Qiang recently visited Ireland in January of 2024 to communicate that “China would like to deepen economic and trade cooperation with Ireland.” What does this Irish-Chinese trade relationship look like at present?

According to the Observatory for Economic Complexity’s most recent trade data, 7.08 percent or $16.7b of total Irish export goods go to China. Of that, nearly 50 percent is in integrated circuits or semiconductor computer chips. Most of these exports come from Intel’s operations in Ireland.

Intel’s CEO announced he hoped to double Irish chip production by 2030. With the recent completion of its Fab 34 site, Intel confirmed, “[doubling] the manufacturing capacity available in Ireland.” The European Union has also incentivized the expansion of its aggregate market share in chip manufacturing of which Ireland is a critical player.

In terms of integrated circuit exports, Ireland is the second largest exporter behind Germany. Ireland is already an established manufacturer of chips and trade partner in them with China. It is not hard to imagine how this sector could be expanded in Ireland.

However, Intel is facing backlash from trade restrictionists in the U.S. that seek to limit trade with China by U.S. firms. This has created headwinds for Intel. However, Ireland is an independent country that has built its economy as an open trading hub. As Pilkington described, in the new era of multipolarity, connectivity to all parts of the world should be a goal for Ireland’s open trading hub model.

While certainly not an overnight process, Ireland should consider how it would go about building up domestic firms that can substitute manufacturing from Intel if it faces further U.S. regulation as the direct manufacturer. Intel could be incentivized to assist Ireland in doing so if it enables them to indirectly expand their strategic interests while getting around burdensome regulation.

As Ireland’s main export destination for chips, China might also consider investing in building up Irish firms that would expand those exports. Ireland’s access to the European Union would also be a key asset for collaboration with Chinese technology firms that may want to use Ireland as a launchpad into Europe.

This strategy has a strong emphasis on manufacturing which contrasts Ireland’s current services-led economy. University of Cambridge political economist Jostein Hauge argued “You'll find potential for value added within all sectors. But again and again, research shows that the manufacturing sector has the highest potential for innovation and trade.”

In fact, Ireland’s initial rise during its Celtic Tiger period can be argued was largely due to manufacturing-led growth. If Ireland were to re-emphasize manufacturing, it would not be out of step with its past. It would also be pursuing a manufacturing sector with increasing global demand and innovation synergies rather than any old manufacturing activity like in textiles.

Red flags have also been raised about the OECD’s corporate tax changes that will equalize Ireland’s low taxes to be on par with the rest of the OECD countries. This will likely harm Ireland’s ability to attract foreign firms to operate in Ireland without this incentive. However, there is a loophole in the OECD’s changes.

The Financial Times reported, “the [OECD tax] rules do not discourage investment in tangible assets such as manufacturing factories and machinery...it may allow companies to pay tax below the 15 per cent rate if they have sufficient real activity in low-tax countries.” This remaining leeway is a window of opportunity for manufacturing expansion.

In summary, Intel’s Irish operations want to expand. China wants to expand trade with Ireland which is mostly in chip production. The European Union wants to expand its chip manufacturing. Ireland’s low tax model is still possible for manufacturing activities but not services. There are many arrows pointing towards a new Irish economic policy that seeks to expand its chip production, create domestic Irish chip firms, and increase its trade with China as its main export destination.

On top of this Ireland has other intangible assets that make a Chinese relationship more conducive. Ireland is a rare western country not part of NATO which provides China with cultural reassurances of ideological similarities. In a more historical sense, China’s ideological anti-imperialism is quite at home in a country like Ireland that’s seen its share of imperialism from England.

Ireland should deeply think about its current economic situation. Its American-centric tax dodging service model is eroding because of the OECD tax changes. Americans also desire to claw back U.S. multinational corporations from Ireland. As multipolarity expands, the U.S. becomes more difficult to deal with and a smaller share of global trade as the rest of the world becomes easier to to deal with and a larger share.

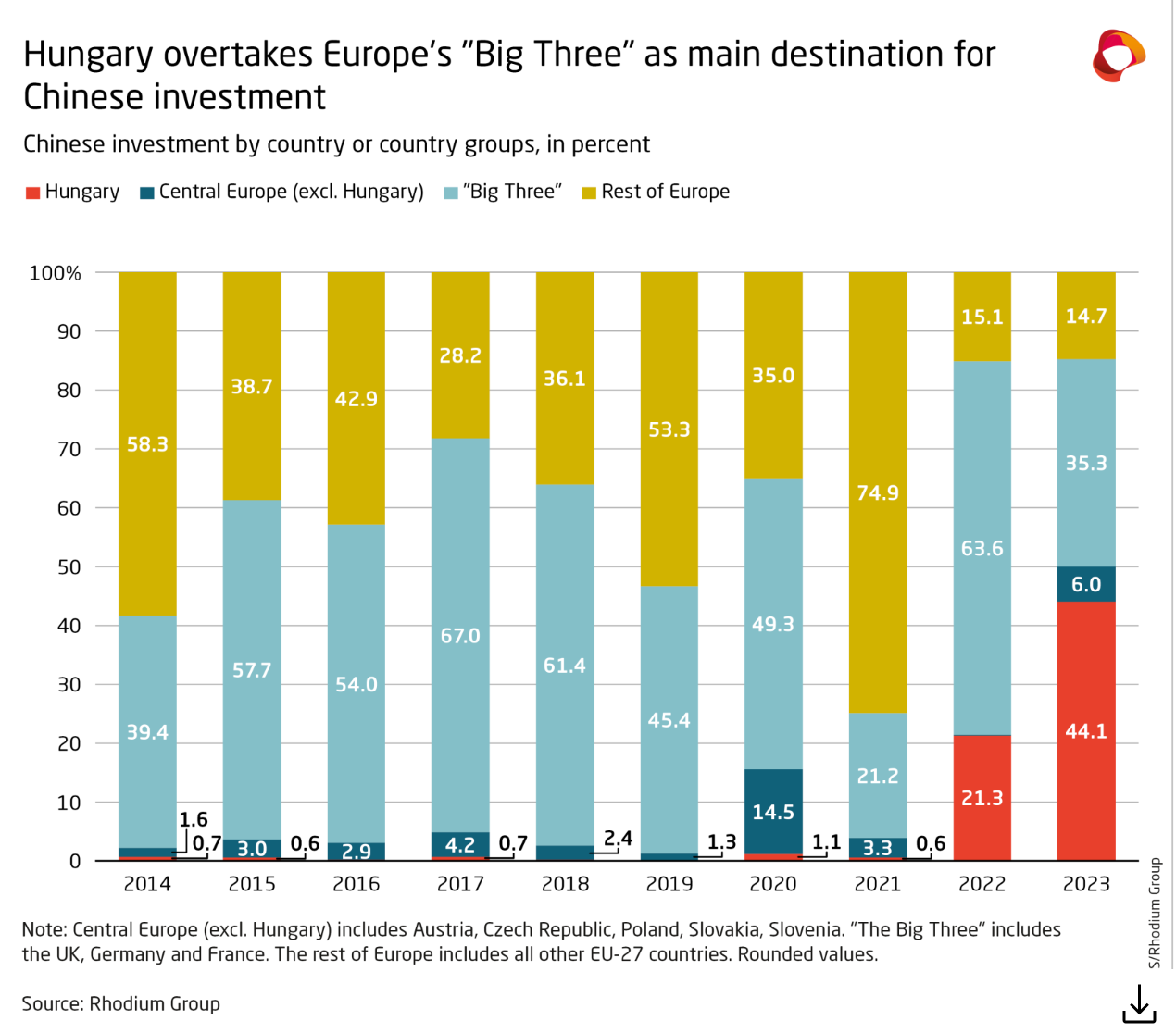

Ireland wouldn’t be breaking new ground in this regard either. Recently, Hungary has followed a similar strategy of building stronger ties with China. According to a Rhodium Group and MERICS report, “Large scale battery and EV investments have led to a dramatic shift in the regional distribution of Chinese investment in Europe, turning Hungary into their primary beneficiary. Investment in the country has skyrocketed in the last two years, up from a very low base. Between 2012 – 2021, average annual investment into Hungary was just EUR 89 million. In 2022, it rose to EUR 1.51 billion, and reached EUR 2.99 billion in 2023…Hungary alone captured 44 percent of all Chinese FDI into Europe, or more than the “Big Three” – France, Germany and the UK – combined.”

Should China and Ireland trade more? That debate should certainly be had in the Dáil. However, for those over-confidently opposed to the idea, perhaps a better question is why do they advocate for Ireland to be more trade isolationist?