Ireland's Foreign Finance Dependency Was Caused By History, Not Economics

A Reply to Fintan O'Toole

There's a central vein that Fintan O’Toole touched on in his Irish Times article “Ireland has had one big idea in the last 64 years.” He argues that Ireland has been bound to the model of foreign capital attraction through “center-right” economics since 1958. Although Ireland generated economic development and high tax revenue, there is a general sense of failure and existential crisis in continuing this model. O’Toole suggests that the problem is now retaining Ireland’s role as a foreign capital magnet which is compromised by a lackluster level of public amenities such as urban metro or a better hospital system. If Ireland doesn’t fix these issues, the lousy living standard relative to labour costs will compel foreign capital to depart Ireland. His unfortunate diagnosis is that Ireland is caught in a catch-22 where it is too ideologically “center-right” to intervene enough in order to increase the level of public amenities to retain foreign capital which is the foundation of Ireland’s “center-right” 64-year-old economic policy. While he is right about the general sense of malaise, why does Ireland have such a myopic obsession and dependency on foreign capital in the first place?

O’Toole dismisses questions like that: “we could have long arguments about whether this is the right or wrong way for a relatively poor country to develop itself. The fact is that this has been the State’s one big idea for the last 64 years – and that it is, right now, spectacularly successful." To him the dye is cast, the cement is dried, and the bread is baked. He doesn’t explain why long arguments are unwarranted but instead unjustifiably commands Ireland to continue down the path of foreign capital prioritization. Yet questioning the economic model is central to resolving the economic problem he identifies. Doing the same mistake over and over again is the definition of insanity.

First, let’s deal with his 64 years claim. While certainly a theme of "openness" to global markets can be suggested, there is much more to it than that. The growth of the 1960s-1970s was caused by excessive borrowing, borrowing from foreigners, high deficits, and low-growth economic activities for development. This caused a bubble to pop in 1979-1983, resulting in negative effects.

The 1980s were a dramatic shift in Irish economic policy. There was a systematic understanding of planning high growth vs low growth econ activity. It was this foundational economic ideology that created the Celtic Tiger which was complemented by foreign capital. There was real growth during the Celtic Tiger because of high growth economic activity which was centered in innovative tech manufacturing fields. The question of foreign capital was secondary to this feature.

Around 1998, the economic ideology shifted and the high growth tech manufacturing was phased out but the foreign capital continued to increase. The bubble, crash, austerity, and malaise of Ireland in the 21st century is evidence of foreign capital itself not being the end-all-be-all. For further documentation of the rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger, read my explainer. The insight to be learned from this 64-year history is that Ireland’s development success has more to do with the state choosing the right economic sectors and directing the capital. In fact, it seems foreign capital created more volatility in Ireland than without it reviewing all ups and downs of the 64 years.

I can hear the squawks now: “but Pete how does a less developed country develop without foreign capital? Where does the money come from? It's never been done before!" Well, I’m sure everyone that makes this claim has surveyed all 500 years of modern global economic development history to assert such a totality. Oh, they haven’t? Then maybe a history lesson is needed to show how a nation can develop without reliance on foreign capital. Let’s use Kenichi Ohno’s “The History of Japanese Economic Development” as our guide.

In 1853, the United States Navy’s Commodore Perry sailed his gunship fleet into the Edo Bay of Japan. The threats of overwhelming military force coerced the Japanese to enter into unfair trade treaties with the U.S. The Japanese realized very quickly that they were severely underdeveloped in comparison to western countries. They were vulnerable to the same imperial conquests observed as near as China and as far as Africa. This pressure resulted in a transformative period of rapid development called the Meiji usually dated between 1868 and 1912. Japan, once seen as a backwater that couldn’t defend itself again Commodore Perry, by 1905, had built one of the premier industrial economies in the world and defeated western Russia in a war that westerners thought was impossible for a non-western country to do.

According to Ohno, “quantitatively speaking, the contribution of foreign savings to industrialization was relatively small during the Meiji period. Almost all necessary funds were raised domestically. Meiji Japan did not welcome FDI or foreign loans for industrialization…There was very little foreign participation in the capital of these companies. In fact, foreigners’ investment in Japanese enterprises (foreign direct investment, or FDI) was prohibited until the commercial law was revised in 1899. Even then, policy and popular opinion remained hostile to FDI.”

Ohno does not leave us a lot of wiggle room. Japan did not rely on foreign capital to develop its economy. The combination of expanded informal finance networks, maturing national private banking sector, growing national stock market, the creation of the Japanese central bank (with a nationalized currency), and government investment (increased by land tax) were the primary origins of capital used for the development of Meiji Japan. The Meiji Japanese government also made conscious choices regarding activity-oriented development and protected the national industry from foreign control. This policy stance was essential to actualizing the quantity of capital raised domestically.

Industrialization was pursued and it was to be national. Whatever foreign assistance was needed, in terms of skilled advisors, technology transfers, etc., was brought in Machiavellianly and, once absorbed by Japanese counterparts, quickly dissolved and spat out. The Meiji Japanese government's role in choosing high-growth economic activities and investing in them was a catalyst for overall growth. These state-owned enterprises were clusters for the private sector to build around. This allowed for the deepening of more complex economic activities too.

The role of activity-oriented economic development can be seen in modern scholarship like from Harvard’s Ricardo Hausman’s work on “The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity”. But you may also find similarity to the above-mentioned way in which Ireland’s government developed in the 1980s: through choosing tech manufacturing activities. In conclusion, foreign capital is not necessary for a nation to develop. It was possible for Ireland to use domestic capital to develop. Ireland's problem was that it could not effectively mobilize domestic financial infrastructure to deploy domestic capital. Why is that?

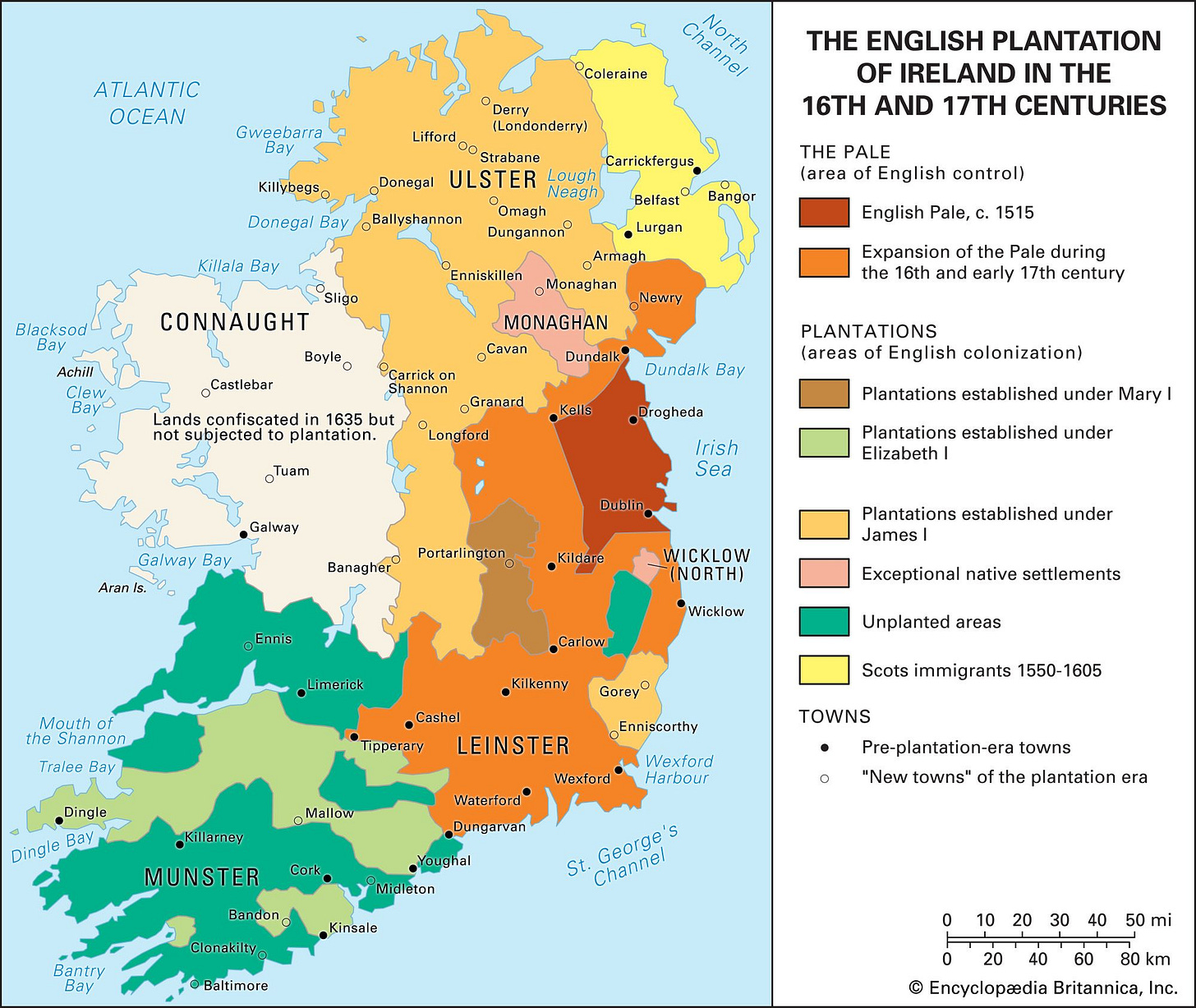

Ireland's role as an imperial colony of England for centuries is the main culprit. Rather than O’Toole’s contention that this is a 64-year-old issue, it’s actually an 800-year-old one. Structural and ideological factors originating from that relationship have shaped domestic finance. Ireland was mainly divided between a native Gaelic-Catholic peasant ethnic-class and a settler Anglo-Protestant elite ethnic-class. The role of Ireland in this context was for the elites to extract raw materials from the land for the benefit of the imperial core (aka England).

This setup meant Ireland was never supposed to develop as other colonies were not supposed to. Capital being used on industrialization in Ireland was an elite non-starter. Industrialization happened in the imperial core. This imperial core theory meant capital flowed to develop the English industry. This meant settler Anglo-Protestant elites in Ireland invested their capital (made off of Irish production) in England.

Obviously, the persecution of native Gaelic-Catholic peasants meant that they had very little ability to develop sophisticated financial infrastructure let alone accumulate savings to be lent out. This persisted for a very long time until the 19th century. This period in Ireland was somewhat of a contradiction. While full of tragedy and oppression, it also contained progressive trends: the liberalizing of legal prohibitions against native Gaelic-Catholics, allowances for limited industry, and mainly farmland transfers to them.

These forces began to shift more and more native Gaelic-Catholics out of peasantry into relative middle class footing. This increased the amount of savings/deposits of Ireland and thus the perceived growth of Irish financial infrastructure. However, "Irish" financial infrastructure was not mobilizing Irish savings to develop Irish industry. It was still investing them in English development. Many Irish nationalists of the 1916-1922 generation stressed this very fact and it was part of why a revolution was needed, such as Sinn Féin’s founder and first President of Ireland Arthur Griffith.

As one might assume, the "Irish" financial infrastructure was dominated by the settler Anglo-Protestant elite ethnic-class. This structural reality shaped an economic ideology that said it was "objective" or "economically sound" to do so. While on the surface it looked as if Ireland had no capital to develop, it was very much the case that Irish savings were not effectively deployed in Ireland as well as further credit expansion. On top of this, high growth activities in Ireland were not desired for what little domestic capital was deployed.

The Irish Revolution and the creation of an independent state would seemingly change this. We can say in part it did as those of native Gaelic-Catholic identity filtered into elite status. However, the structural reality of many settler Anglo-Protestant elites still in dominant positions of Irish society (especially finance) meant that the status quo was maintained in part.

The economic ideology that was shaped by the above structural reality remained unchallenged and seen as an objective science. As the passions of revolution quieted, native Gaelic-Catholics passively inherited much of the same economic ideology that was derived from the English empire because no radical revolution occurred in the elite institutions. As the 20th century rolled on, many hardline Irish nationalists criticized the lack of economic protectionism and private financial investment that were components of the rallying cry for Irish independence.

Finally, we can clearly see why there was a financial hole that created the need for foreign capital 64 years ago. It is that hole that continues to dictate Irish policy to this day and into the future. It appears that Japan had an easier go of unifying and mobilizing domestic capital because it did not suffer from an imperial history and thus a two-tiered ethnic-class society. Unfortunately, Ireland has never truly reconciled this imperial history of a two-tiered ethnic-class society. And until it does it will keep repeating the mistakes. Until it does, it will never question the foundation of economics it sees as science. Until it does, it will continue to shape future economic policy using the argument that "Ireland tried protectionism and the like and it was terrible so we can only go this one way."

That historical argument is incorrect and fails to account for the economic public and private policy trends that coincided with that era. Also, it fails to appreciate the departure of Eamon de Valera’s attempt at protectionism with Arthur Griffith's original protectionism and global protectionist orthodoxy. Mary E. Daly's "Industrial Development and Irish National Identity, 1922–1939" documents the key details of de Valera’s failed protectionism well. You can also read my work detailing Irish revolutionary economic ideology. Thus the real conclusion of that era is that protectionism was never really done at all and imperial elite economic ideology roughly maintained.

The policy takeaway is that the Irish private banking sector should be regulated to increase the quantity of credit and the direction of that credit into sustainable growth areas of industrialization. The state must also play a role in capital deployment and management of state enterprises. Ireland will achieve things like urban metro, better healthcare, water management, etc. that O’Toole desires through nationalized high growth with smart state direction of the economy not the attraction of foreign undirected capital. Ireland's foreign capital dependency was caused by history, not economics.