Irish Electricity Prices Explained: How Neoliberalism Backfired in Energy Sector

Ireland has some of the highest — if not the highest — nominal electricity prices across Europe.

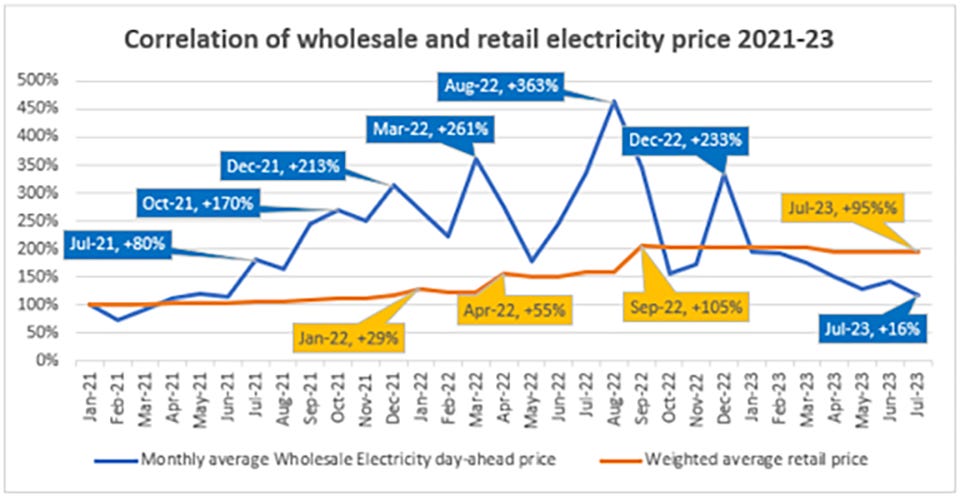

The energy crisis over the past two plus years was primarily caused by the disruption of Russian oil and gas exports. The contraction in supply of these critical inputs to electricity systems resulted in elevated wholesale and retail electricity prices.

The operators of the Irish electricity system have therefore come under scrutiny from politicians. They are criticized for not doing enough to lower prices relative to the rest of Europe and taking excessive profits during the crisis. However, the operators are being unfairly maligned after performing to the best of their ability in a very constrained environment.

The true blame should be placed on the Irish government because of its haphazard regulations on the electricity sector – and its incompetent green energy plans.

As we will see, the state’s decision to deregulate the energy market and to force a division between Electricity Supply Board (ESB) and Electric Ireland has led to a situation where these entities are prevented from acting to lower prices for the hard-pressed Irish consumer.

ELECTRICITY PRICES

First, let’s review Irish retail electricity prices and European retail electricity prices sourced from Eurostat’s most recently updated data up until August 2023. The optimal metric to focus on is, according to Eurostat, “the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) [which] gives comparable measures of inflation for the countries and country groups for which it is produced.

It is an economic indicator that measures the change over time of the prices of consumer goods and services acquired by households. In other words, it is a set of consumer price indices (CPIs) calculated according to a harmonised approach.

The data has been filtered to only focus on electricity prices. For context, this was the metric used by Sinn Fein’s Pearse Doherty when he criticized the high prices a couple months ago. Ireland’s Central Statistics Office (CSO) was also used to corroborate Eurostat’s data.

From the start of the crisis in January of 2021, the average of the European Union retail electricity prices increased by 42 percent vs. Ireland’s 93 percent. The monthly average rate of change was 1 percent for the European Union average vs. 2 percent for Ireland.

Source: Eurostat, Ryan Research

Ireland’s retail electricity prices increased at more than double the rate of the European average. Countries like Germany and France were able to keep their prices below the average, while countries like Norway and Italy actually performed worse than Ireland during the crisis.

As the crisis went on, Ireland’s prices grew faster. In the first year, Ireland’s prices grew at 22 percent which was lower than the 28 percent European Union average. In 2 years, Ireland’s prices grew by 99 percent compared to the European Union average of 53 percent. As noted previously, the total change for Ireland was 93 percent vs. the European Union average of 42 percent. Over these years, Ireland moved from a rank of 13th out of 35 countries, studied by Eurostat, to 6th and finally 3rd. It ranked 7th place in terms of monthly average.

Source: Eurostat, Ryan Research

There are elevated prices in general but it is worth noting that Ireland was moderately better at handling price spikes in the early periods of the crisis. This trend of Ireland performing better earlier and worse later is symptomatic of Irish operators, especially Irish electricity suppliers to retail consumers, buying hedged futures contracts.

This meant that they locked in the future prices of their inputs months to years in advance to avoid real-time market swings to even higher prices. They would be protected from the downside of sharp increases in wholesale prices but, by the nature of the deal, upside from lower wholesale prices would be inaccessible to them.

If wholesale prices consistently decreased, retail prices would lag because they would have to wait until the conclusion of the hedged contract’s term.

The Irish regulatory entity responsible for the electricity market is the Commission for the Regulation of Utilities (CRU).

After its investigation into the criticisms levied at the operators it wrote, “the CRU sees no prima facie evidence at this stage of market failure in retail markets…Retail prices are broadly continuing to reflect underlying cost drivers, but at a lag due to supplier hedging…supplier hedging significantly reduced the impact to consumers of the sustained high and volatile prices in the wholesale market, during the period in advance of and during Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This slower and smoother increase, facilitated by hedging, is expected to be mirrored by similar slower and smoother decrease should wholesale and futures prices continue to decline.”

Source: Commission for the Regulation of Utilities (CRU)

It also specified that “generators and suppliers generally take a long-term perspective (1 – 2.5 years) rather than a short term (monthly – quarterly) perspective when setting consumer’s prices. Companies employ this type of hedging strategy to increase certainty and help mitigate against exposure to adverse price movements in the future.”

According to CRU data, these hedging strategies were able to keep Irish retail prices relatively protected from proportional changes seen in Irish wholesale prices. Similarly, the protection occurred in the early periods and reversed in 2023. As other scholars have noted, Irish operators are more likely to hedge and hedge for longer durations.

The double edged sword is that while those long duration hedges don’t reflect sudden market increases in the wholesale prices, they also don’t reflect sudden market decreases. It is expected that the recent wholesale price reductions will be reflected in 2024 retail prices. This is due to old higher priced hedges expiring and replaced with new lower priced ones. However, other mitigations are being proposed by Irish electricity operators and the Irish government to reduce them sooner.

It is worth asking the question if you are very keen on the necessity of current wholesale prices to be reflected in current retail prices, then would you be as keen for retail prices to equate to wholesale prices at the earlier dates where they grew significantly more?

Obviously, the answer is no and we can conclude that hedges can be a worthwhile strategy. It was difficult to predict if and when wholesale prices would come down. It’s not at all an unwise estimation to have expected further increases. Although, since prices did come down — thanks in large part to the United States bailing out Europe with liquified natural gas (LNG) — such hedging appears less desirable with hindsight.

However, as we will now examine, what most consumers might not realise is that the state, by regulating the energy market in a certain way, has forced ESB and Electric Ireland into an awkward position with the aforementioned hedges – and the regulations imposed on both entities forbid them to set aside the contracts and lower prices for the consumer.

ROLE OF REGULATIONS

The big picture here is that Irish electricity operators have long struggled to deliver optimal results due to factors outside of their control and that long pre-date the energy crisis.

For example, ESB and Electric Ireland were once a single entity. However, government policies to liberalize the Irish electricity market forced them to split to promote competition and free markets.

Under the terms of their licenses, they can’t cooperate which would indicate anti-competitive behavior due to their legacy as a state utility monopoly. Thus, there is more scrutiny placed on them and a tendency to for worse performance to assure pro-competition regulatory compliance.

Source: Ryan Research

ESB’s Chief Financial Officer Paul Stapleton noted, “ESB could not subsidise its retail arm Electric Ireland to offset prices for customers here as it was forbidden from doing so under the terms of its licence.”

The irony of the situation is that both ESB and Electric Ireland are still technically Irish state-owned companies. The state’s liberalization policies force them to not collaborate on lowering prices because that would be anti-competitive. The state’s liberalization policies force them to not share finances because that would be anti-competitive.

The very long duration hedges, which Electric Ireland has taken out, are with ESB. These hedges — where both parties are in actuality just the Irish state itself — could be voided through the state but that would be anti-competitive and against the liberalization policies.

The voiding would enable current lower wholesale prices to be reflected in current retail prices because suppliers wouldn’t be beholden to their hedged contracts. The government could also subsidize the losses on those contracts.

Ireland has the worst of both worlds. It has too much government regulation preventing ESB and Electric Ireland from lowering prices because that very regulation is promoting deregulation and market forces.

ESB PROFITS

The next criticism levied was that the operators were profiting too much. This criticism fixated on the ESB’s 2022 profit of €847m (up 25 percent from the prior period) and its 2023 interim 6-month profit of €676m (up 30 percent from the prior period).

The 2022 annual profit was offset by the little publicized €327m (38 percent of the total) dividend paid to the Irish government, since the Irish government is the majority shareholder of ESB. The adjusted profit value is €520m.

ESB’s interim 6-month report noted €779 million in capital expenditure (up 46 percent from the prior period). This investment will go towards improvements in energy infrastructure with an emphasis on the much clamored for renewables. In addition, much of its interim 6-month profit was produced by its Carrington power plant located in the United Kingdom due to the specifics of the plant operations and the UK market.

ESB’s 2022 profit was nullified by significantly higher dividends paid to the Irish government and investment in Irish energy infrastructure in line with Net Zero goals. An increase in the partial year profit had nothing to do with the specifics of the Irish market as well.

Finally, ESB is not directly responsible for retail electricity prices because it is not a supplier. According to the CRU report, “SSE Airtricity, BGE and Electric Ireland, who supply over 80% of domestic electricity customers in Ireland, either returned profits to customers, or made losses.”

In fact, Electric Ireland voluntarily forwent its 2022 profit and gave it back to consumers to lower their prices. When taken all together, the accusations of obscene profit taking by operators is very dubious.

It’s astonishing that Irish politicians can take a huge dividend from ESB and still whine about alleged bad behavior of the operators who are simply managing the best they can under the conditions set by the state. In the cases shown, the operators have gone out of their way to voluntarily offset any perceived gains made during the crisis.

ROLE OF GREEN ENERGY

The state’s incompetence doesn’t just stop at electricity market regulatory policy. If you want to know why the nominal electricity prices of Ireland consistently rank at the top of the EU, even before the crisis, then look no further than the Irish state’s incompetent policy on green energy.

The Irish state has pushed the Irish energy system towards unreliable wind energy now making up 30 percent of electricity generation. While doing so, it has at the same time sabotaged traditional fossil fuels in Ireland.

In 2021, the state banned all domestic exploration and drilling for oil and natural gas in Ireland’s offshore waters despite those waters once supplying 100 percent of Irish natural gas needs. Just this past month, the Irish state prohibited construction of a liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal.

A research paper, authored by Oosthuizen & Co., published in Energy, an international, multi-disciplinary journal in energy engineering and research, found “a positive coefficient from the share of renewable energy to average retail electricity prices which means that an increase in the [renewable] share led to increases in the prices for the 34 OECD countries for the period 1997–2015.”

Ireland’s green energy approach both excessively emphasizes unreliable wind energy and deemphasizes reliable fossil fuels more so than the vast majority of European countries. For instance, although the rest of Europe is pursuing green energy agendas, they are planning to increase LNG import capacity by one-third.

In addition, Ireland has long neglected modernizing its energy sector with the introduction of nuclear power which reliably and cheaply supplies countries like France and Sweden. Ireland has high retail electricity prices because it has bad energy generation policy which is compounded by haphazard liberalization policy leading to the dysfunction of a system that could have produced cheaper prices.

CONCLUSION

Calls for a windfall tax on the operators are unwarranted considering the operators’ profits were already effectively at zero or losses because they funneled them to consumers through cost savings, dividends to the state, or investments in infrastructure. The reputations of the operators should not be tarnished because of the fleeting political fancies of an incompetent political class wanting to make hay out of a crisis.

The straight-forward solution to the current problem is to allow for the fair play of the rules of the game which would lead to decreased retail prices in accordance with hedged contracts expiring.

A more creative solution would be for the Irish state to streamline the electricity market by removing the liberalization regulatory blockages preventing price reductions. This would allow for the voiding of the hedges immediately. It should do this along with emphasizing fossil fuels through opening drilling backup and allowing the LNG terminal to be built as well as introducing nuclear energy proposals.

Originally published on Gript on October 10, 2023.