Introduction

This list should provide an education for those seeking to be full stack economists. I define full stack economists as those who seek to manage a nation's economy from a holistic and entrepreneurial framework. Borrowing from the software concept of the full stack developer — a developer that has mastered all major areas of coding — the full stack economist is an economist that has mastered all major areas of the economy. In contrast to myopic theoretical economists, full stack economists are interested in action, growth, and versatility. Instead of over-specialization, a full stack economist sees the economy as an interconnected system and thus one aspect cannot be ignored as it affects all other aspects of the economy.

This list is not supposed to be restatement of the top search results for “economics books.” You don’t need me to tell you to read Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes. The obvious canon of economics is both valuable while insufficient. I also don’t need to tell you to learn calculus, statistics, and data science. This list is to provide you with works that you might not otherwise come across yet hold tremendous insight. In addition, these works will lean towards historical empiricism and practical applicability. I’ve avoided any works before 1950, as this list is intended to be somewhat easily digested. Older works are immensely valuable but for the sake of this list’s intention to be an introduction, avoidance of outdated writing styles, turgid prose, or esoteric contextual knowledge will be helpful.

It is laid out in the order it should be read, and divided by first principles and case studies. The first principles section explores thematic and historical books that ground the reader with important concepts and historical context. The case studies review exactly how specific countries economically developed and note the successes and failures of each process. I’ve always found a void of case studies in traditional economic education. Theory can only take you so far and thus one cannot fully understand economics without knowing the play by play dynamics of unique countries with unique challenges. Mike Tyson said “everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” Similarly, every economist has an economic theory until an invading army conquers your country. Decision making doesn’t happen on a chalkboard in an ivory tower, it happens in time-limited and resource constrained contexts with internal and external entropic pressures. This list will be a helpful guide for those seeking to be full stack economists.

List

First Principles

1. 1000 Castaways by Clint Ballinger

Ballinger provided an excellent introduction. The use of island metaphors is often used to elucidate basic concepts in economics given its simplicity. Ballinger takes this to the next level. He expands the island metaphor into an entire book that walks the reader through how societies are formed and developed. In doing so, the reader is provided with an accurate description of the private-public sector dichotomy and the role of money. Ballinger excels at explaining money and its centrality to the proper functioning of societies. The core takeaway is an accurate conceptual model of how society works, from an economic perspective, that can be built upon by later books. I’ve had the good fortune to speak with Ballinger and host him on my podcast. You can listen to that episode here.

Quote from the book: “The banking system is only a little about creating a private monetary system. The far more important role it carries out is allowing for the organization of private productive enterprise on scales unimaginable in societies without such systems. This makes the material wellbeing of society many times greater, providing many times more material goods such as food, clothing, entertainment, and services.”

2. When Histories Collide: The Development and Impact of Individualistic Capitalism by Ray Crotty

After establishing a conceptual foundation, Ray Crotty’s historical magnum opus is an essential education in wedding a conceptual foundation to the specifics of the historical process. Many people simply don’t know real history. They have myths and narratives about history. They don’t know how the world, let alone unique societies, came to be what it is today. Crotty presented a detailed and encompassing articulation from the beginnings of the human story to our present. One of Crotty’s strengths is the practical discussion of agriculture. The reader is grounded in the harsh human reality of sustenance and how the pursuit of calorie production shaped societies. Crotty constantly reminds the reader that societies don’t just appear and exist but are outcomes of material calculations of crop yields and caloric demand.

According to Crotty, societal forms are downstream from the mode in which societies produce calories which themselves are downstream from the environment of a given society. Crotty placed special emphasis on how western individualistic capitalism was uniquely formed as a combination of lactose tolerant cattle herding and the moderately fertile yet “limitless” forested geography of the European peninsula opposed to other regions where collective modes utilized high fertility crop growing riverine lands. Crotty is a superb authority because he worked as a farmer, received advanced academic training, and worked as a World Bank advisor for developing countries for decades. Crotty extended his analysis into the modern industrial era and while that is useful, the core takeaway is his examination of pre-industrial history. The specifics of his pre-industrial history provide the necessary foundation to understanding industrial history. As a special note, out of all the books I’ve ever read, this book contains the most highlights and notations.

Quote from the book: “The realization of the potential inherent in the combination of lactose tolerant pastoralists and limitless arable land freed humanity from dependence on the extent and fertility of the land available and the state of the art. It made society dependent instead on the efforts and ingenuity of individuals in extending the cultivated area. That transformation of circumstances, which made people no longer absolutely dependent on socially controlled natural resources, but made society instead dependent on the efforts of individuals to mobilize limitless natural resources, was the emergence of individualism.”

3. And Forgive Them Their Debts by Michael Hudson

Michael Hudson’s premier contribution is the collection of evidence he brings to the discussion of the origin and role of money. Rather than relying on assumptions about money’s origin in history, Hudson examined archaeological evidence to prove or disprove assumptions about money. The dominant narrative is that money emerged from decentralized barter exchange, however, Hudson argued there is clear evidence of state created money through debt in the earliest civilization in ancient Mesopotamia. Hudson based this book on his much earlier research which was also a major influence on the more popular work Debt: The First 5000 Years by David Graeber.

The reader takes away an evidence-driven account of how early societies created money, for what purpose, how it was managed for the benefit of society, how it evolved over time, and how that shapes our current approaches to money. Hudson raised the distinction that debt is an artificial abstraction and is not bound by natural laws. Thus, debt can’t be treated as something apart from man’s artificial manipulation in contrast to conventional views that debt is somehow in the same realm of thermodynamics. This has important implications for our heavily financed contemporary societies. As a word of caution, Hudson experimented with explanations of how economics intersected with ancient religions, however, that shouldn’t detract from his expansive scholarship and main thrust of his text.

Quote from the book: “A study of the long sweep of history reveals a universal principle to be at work: The burden of debt tends to expand in an agrarian society to the point where it exceeds the ability of debtors to pay. That has been the major cause of economic polarization from antiquity to modern times. The basic principle that should guide economic policy is recognition that debts which can’t be paid, won’t be. The great political question is, how won’t they be paid?”

4. Where Does Money Come From? by Josh Ryan-Collins, Tony Greenham, Richard Werner, and Andrew Jackson

This group of authors returns us back to more conceptual lessons rather than deep histories of the prior two. This is a very digestible book that walks the reader through these basic questions around money. It will be apparent how useful the foundation of Ballinger and Hudson is in following along with this book. They place an emphasis on the private banking sector’s special role in money creation. They point out how there are many incorrect assumptions about money and its connection to banking that diminish the efficacy of policies. They often argue that contrary to popular belief, most of the money in circulation is not issued by central banks but rather created by commercial banks when they issue loans.

An implicit secondary question that the book asked is “Where does money go?” The authors explained that there are objective divisions between productive and speculative credit allocation. This provides the reader with a valuable framework of understanding that qualitative decisions and their associated quantitative allotments matter greatly. After understanding the mechanics of the monetary process, the authors argued it is viable for sovereign countries to not require any external financings as it can be entirely created in their own domestic monetary systems. A special emphasis is placed on the U.K. context.

Quote from the book: “In reality, the tail wags the dog: rather than the Bank of England determining how much credit banks can issue, one could argue that it is the banks that determine how much central bank reserves and cash the Bank of England must lend to them (Section 4.3). This follows on from the Bank’s acceptance of its position as lender of last resort…When a commercial bank requests additional central bank reserves or cash, the Bank of England is not in position to refuse. If it did, the payment system described above would rapidly collapse.”

5. New Paradigm in Macroeconomics by Richard Werner

Werner was a co-author on the previous book, and this one acts as a more advanced version of the former. Werner formally expanded on the crux of both works which is his Quantity Theory of Credit — Unproductive credit creation (for non-GDP transactions) will result in asset price inflation, bursting bubbles and banking crises as well as resource misallocation and dislocation. In contrast credit used for the production of new goods and services, or to enhance productivity, is productive credit creation that will deliver non-inflationary growth. His ideas are backed up by his heavy use of data and empirical research. He has unique expertise in deriving insights from the Japanese financial bubble of the 1980s-1990s that forms an important common thread to his book. The reader should take away a more sophisticated understanding of money and banking while also attaining a tool kit of how to structure effective money and banking policies.

Quote from the book: “We can now proceed to apply this finding of the pervasiveness of market

rationing to the credit market. Since due to imperfect information also the credit market will be rationed, it will be determined by the quantity (according to the short principle), and not the price. This explains the empirical fact that interest rates have not been very useful as explanatory or predictive variables of either economic activity or, indeed, money and credit growth.”

6. The Entrepreneurial State by Mariana Mazzucato

Mazzucato is one of the most influential living economists today. Her work is already widely cited and deserves to be read by any aspiring economist. She firmly asserted the critical role of the state in nurturing the private sector to excel. She shattered dominant neoliberal dogmas that diminished the state’s role and popularized a return to the thinking that originally developed economies during their industrial transitions where the state was indispensable. She focused on examples of how the state led innovation, notably the components of the iPhone being almost all derivatives of government funded projects. The book advocates for a reimagined role of government as an entrepreneurial force in the economy, shaping long-term innovation policies that ensure sustainable growth and fair rewards. The reader will see how after absorbing the previous lessons on money, Mazzucato offers a methodology of how to allocate and invest money for a productive economy.

Quote from the book: “innovation economists from the ‘evolutionary’ tradition (Nelson and Winter 1982) have argued that ‘systems’ of innovation are needed so that new knowledge and innovation can diffuse throughout the economy, and that systems of innovation (sectoral, regional, national) require the presence of dynamic links between the different actors (firms, financial institutions, research/education, public sector funds, intermediary institutions), as well as horizontal links within organizations and institutions (Lundvall 1992; Freeman 1995). What has been ignored even in this debate, however, is the exact role that each actor realistically plays in the ‘bumpy’ and complex risk landscape. Many errors of current innovation policy are due to placing actors in the wrong part of this landscape (both in time and space). For example, it is naïve to expect venture capital to lead in the early and most risky stage of any new economic sector today (such as clean technology). In biotechnology, nanotechnology and the Internet, venture capital arrived 15–20 years after the most important investments were made by public sector funds. In fact, history shows that those areas of the risk landscape (within sectors at any point in time, or at the start of new sectors) that are defined by high capital intensity and high technological and market risk tend to be avoided by the private sector, and have required great amounts of public sector funding (of different types), as well as public sector vision and leadership, to get them off the ground. The State has been behind most technological revolutions and periods of long-run growth. This is why an ‘entrepreneurial State’ is needed to engage in risk taking and the creation of a new vision, rather than just fixing market failures. Not understanding the role that different actors play makes it easier for government to get ‘captured’ by special interests which portray their role in a rhetorical and ideological way that lacks evidence or reason. While venture capitalists have lobbied hard for lower capital gains taxes (mentioned above), they do not make their investments in new technologies on the basis of tax rates; they make them based on perceived risk, something typically reduced by decades of prior State investment. Without a better understanding of the actors involved in the innovation process, we risk allowing a symbiotic innovation system, in which the State and private sector mutually benefit, to transform into a parasitic one in which the private sector is able to leach benefits from a State that it simultaneously refuses to finance.”

7. How Rich Countries Got Rich ... And Why Poor Countries Stay Poor by Erik S. Reinert

This is one of the best explanations of economic growth. Instead of treating economic growth as some sort of intangible mystery, Reinert explained the key to wealth creation. His core theory is that economies grow because they collectively focus their efforts towards activities that provide increasing returns to scale. Thus, this is a very measurable phenomenon and policy can be crafted around activities that provide such results. Reinert is in part criticizing mainstream economics that constrains the theories of growth to abstract capital accumulation and efficiency in resource allocation, devoid of qualitative analysis of economic activities. Reinert also walks the reader through different case studies to elaborate his theory. He takes the reader to Mongolia, Germany, Ireland, and more to show where countries get it right and where they get it wrong. The reader should take away a very clear understanding of how economies grow.

Quote from the book: “the key mechanism to wealth is not manufacturing per se, but activities subject to increasing returns, technological change, and consequent dynamic imperfect competition under high barriers to entry…Generally increasing returns goes with imperfect competition; indeed, the falling unit cost is one cause of the market power under imperfect competition. Diminishing returns – the inability to extend production (beyond a certain point) at falling cost – combined with the difficulty of product differentiation (wheat is wheat, while car brands are very different) are key elements in creating perfect competition in the production of raw material commodities. The exports of the rich contain the ‘good’ effects – increasing returns and imperfect competition – whereas traditional exports of poor countries contain the opposite, the ‘bad’ effects.”

8. Kicking Away the Ladder by Ha-Joon Chang

Ha-Joon Chang’s “Kicking Away the Ladder” is a great follow up to Reinert’s book. It expands on Reinert’s theme of better understanding economic development. Chang provided a historical analysis of how many different countries developed. Notably, he focused on the recent East Asian high growth economies and ties them in with the period of European and American industrialization in the 18-19th centuries. He concluded that all countries that develop to advanced standards at some point employed protectionist policies and that free trade only becomes relevant at the end of this process. Free trade, according to Chang, can often act as a subversive theory that sabotages competitor nations from attaining the same development level of the dominant nation or nations. He leveraged a lot of history to make his case and highlighted the 19th century economist Friedrich List as a major influence. He also provided specific outlines of what these protectionist policies were and how various contexts might call for less or more of them.

Quote from the book: “Surveying the postwar experiences of the East Asian countries, we are once again struck by the similarities between their ITT [Industrial, Trade, and Technology] policies and those used by other NDCs [Now-Developed Countries] before them, starting from eighteenth-century Britain, through to nineteenth-century USA, and late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Germany and Sweden. However, it is also important to note that the East Asian countries have not exactly copied the policies that the more advanced countries had used earlier. The ITT policies that they, and some other NDCS like France, used during the postwar period were far more sophisticated and fine-tuned than their historical equivalents. The East Asian countries used more substantial and better-designed export subsidies (both direct and indirect) and in fact imposed very few export taxes in comparison to the earlier cases. As I have repeatedly pointed out, tariff rebates for imported raw materials and machinery for export industries were widely employed – a method that many NDCs, notable Britain, had themselves used to encourage exports. Coordination of complementary investments, which had previously been done in a rather haphazard way, if ever, was systematized through indicative planning and government investment programmes. Regulations of firm entry, exit, investments and pricing were implemented in order to ‘manage competition’ in such a way as to reduce the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century century cartel policies, but displayed far more awareness than their historic counterparts of the dangers of monopolistic abuse, and more sensitivity to its impact on export market performance. There were also subsidies and restrictions on competition intended to help technology upgrading and a smooth winding down of declining industries. The East Asian governments also integrated human-capital-related and learning-related policies to their industrial policy framework far more tightly than their predecessors had done, through ‘manpower planning’. Technology licencing and foreign direct investments were regulated in an attempt to maximize technology spillover in a more systematic way. There were serious attempts to upgrade the country’s skill base and technological capabilities through subsidies to (and public provision of) education, training and R&D.”

9. The Atlas of Economic Complexity by Ricardo Hausmann

After the absorption of the prior histories, theories, and policy outlines, Ricardo Hausmann can provide the next step in a more modern and technical application of the same developmental themes. Hausmann harnessed high volumes of data to argue that economies grow due to complexity. The more complex an economy is, the more advanced it is. Thus, economies should seek to develop more complexity. Secondly, the diversity of activities in an economy is mappable in relation to one another. Hausmann suggested that this map can be used to identify paths of development. These paths may be different for various countries because they seek to identify the current activities of a country and show the most accessible technologies and products they can make to add more complexity. The shorter distance between activities means that new activities are more likely to succeed rather than one farther away in the product map. This provides economists with an amazing level of clarity in planning out development. Hausmann also has a website by the same name that acts as an interactive data tool that is essential.

Quote from the book: “Over time economic complexity evolves: countries expand their productive capabilities and begin to make more and more complex products…consider that making a product that is new to a country requires the addition of all missing capabilities. Adding a product for which a country needs many new capabilities often proves difficult because it requires solving a complicated “chicken and egg” problem. An industry may not exist because the productive capabilities it requires may not be present. But there will be scant incentives to develop the productive capabilities required by industries that do not exist. Furthermore, developing those capabilities will be difficult because there is nobody in the country from which to learn the requisite know-how. Because of this problem, countries tend to preferentially develop products for which most of the requisite productive capabilities are already present, leaving fewer “chicken and egg” problems to be solved. We say that these products are “nearby” in terms of productive capabilities. What differs between countries is the abundance of products that they do not yet make but that are near their current endowment of capabilities. Countries with an abundance of such nearby products will find it easier to deal with the chicken and egg problem of coordinating the acquisition of missing capabilities with the development of the industries that demand them. This should allow them to find an easier path towards capability acquisition, product diversification and development. Countries with few nearby products will find it hard to acquire more capabilities and hence to increase their economic complexity.”

10. Communism and Nationalism: Karl Marx Versus Friedrich List by Roman Szporluk

Within this list, there may seem like an over-emphasis on the role of the state and an overly-critical perspective of the conventional free market theory. However, now that enough of the foundation has been provided, Roman Szporluk can provide a palette cleanser. He examined the similarities and differences between communism and nationalism (the ideology most closely aligned with this list). In doing so, he dilenates a clear separation in ideas between the two schools of thought. He also highlighted the close connection between industrialization and nationalism that was often devoid in communism. Thus, when seen in this light, this list is not so overly critical of the market nor overly reliant on the state. All societies have states and so knowing the proper use of it is really the intention. Any reader that was anxious about the debunking of free market myth should be comforted after reading Szporluk that in many ways the ideology suggested by this list is pro-market and conversely, that communism explicitly opposed nationalism. Fair warning, this is a very academic book but if you’ve read this far you should be well versed to handle it.

Quote from the book: “The "national economists" criticized free trade as an instrument of England's policy to preserve its industrial supremacy. They argued, as a modern scholar, Bernard Semmel, has put it, that the "science" of political economy and the principle of so-called "cosmopolitanism" had been "designed to keep the non-British world in the humiliating and economically inferior position of serving as suppliers of food and raw materials—mere hewers of wood and drawers of water—to a British industrial metropolis."36 The first of the national economists was Alexander Hamilton, who as American Secretary of the Treasury presented to Congress a "Report on Manufactures" in 1791. "The labor of artificers,'' according to Hamilton,' 'being capable of greater subdivision and simplicity of operation than that of cultivators," ought to be improved in "its productive powers, whether to be derived from an accession of skill or from the application of ingenious machines.'' Hamilton further argued that preferring foreign manufactures over domestic ones amounted to passing onto foreign nations "the advantages accruing from the employment of machinery." Hamilton believed, according to Semmel, that "the inherent nature of trade between an agricultural and a manufac- turing country placed the former at a considerable disadvantage." Accordingly, Hamilton asked Congress to enact protective and supportive measures to "the degree in which the nature of the manufacturer admits of a substitute for manual labor in machines." Hamilton did not want America to depend on Europe for manufactures; it ought to possess "all the essentials of national supply."

11. Order Without Design by Alain Bertaud

As a natural complement to Szporluk, Alain Bertaud will offer a great defense of market oriented ideas. Again, I hope this dispels any anxiety to those that feel an anti-market sentiment in this list. Bertaud is a great defender of market ideas because he is very methodical and applies them in a scientific manner rather than in an abstract disconnected way. Bertaud’s book is about urban planning. While that may seem niche, it is a great case study to explore these ideas. Bertaud has decades of experience of being an urban planner with the World Bank and has worked in many cities across the world. There are few people on Earth with such a resume to speak as authoritatively as he does. Bertaud will teach the reader how to critically think about problems on a case by case basis. The reader will learn what tools and data to use for each case, and when to apply more of a market solution. It’s important to note that market solutions are still state policies made by the decision-making of economists. After the foundation of the earlier books, I find this nuanced pro-market book balances out the ideas while not taking away nuance or erasing the earlier lessons.

Quote from the book: “The productivity of cities therefore requires both concentration of people and high mobility. When the time and cost required to move across a city increase, mobility decreases. When this happens, workers have fewer choices among the potential jobs available in a city, and firms have fewer choices when recruiting workers. In these conditions, metropolitan labor markets tend to fragment into smaller, less productive ones; salaries tend to decrease, while consumer prices increase because of lack of competition.”

12. Super Imperialism by Michael Hudson

Michael Hudson’s “Super Imperialism” can provide the reader with a clear understanding of the current state of international economics. It combines some of the previous lessons learned into an analysis of the current world order and how that shapes economics. Hudson sometimes takes a critical perspective at certain countries but as the finale of the first section of this list, I find that it is a necessary criticism. A full stack economist must have a realist understanding of how the world works. One can’t be lost in a fantasy that other competitors and dominant powers will be friendly or have your country's best interest in their hearts. On another note, the core point of the book is to explain how the U.S. dollar system since the 1970s has created the artificial laws of economics that all countries follow today and how that system may collapse in the coming future.

Quote from the book: “In taking this position the United States enjoys an alternative that other countries have not been able to duplicate. Thanks to the large size of its domestic market it can “go it alone.” Its financial claims and the superstructure of dollar debts that now permeate the world economy – taken in conjunction with the high levels of direct investment in America by foreigners – mean that a U.S. move towards autarchy would fracture the world financial system. The specter of bringing on such a collapse has given U.S. diplomats an option not available to nations whose economies are more highly dependent on smoothly functioning international commerce and payments. Foreign trade accounts for only about 5 per cent of America’s GNP, compared to some 25 per cent for many European economies. Foreign central banks held over a trillion dollars in U.S. Treasury securities. Until Europe and Asia are able to replace the Dollar standard with a currency system of their own, and until they are willing to run the risk of a trade and investment war as an intermediate step toward achieving their own self-sufficiency, the U.S. economy will have little reason to feel that it needs to live within its means.”

Case Studies

13. The History of Japanese Economic Development by Kenichi Ohno

Now that all the lessons have been learned, these historical case studies serve as a way to see those theories in action. While there were elements of history in the previous books, these books will provide a hyper-focus on one particular country or policy theme. Kenichi Ohno wrote a fantastic and sweeping economic history of Japan. Japan in many ways is the model nation for applying correct development policy. Ohno discussed the domestic precursors that either harmed Japan’s ability to develop or prepared it to do so before its critical mid 19th century inflection point of the Meiji Revolution. He then explained how each aspect of the modern Japanese economy came about and whether there was state or market-led development. The conclusion is obviously that it was a mixture of both but this doesn’t stop a key insight being that Ohno clearly articulated the protectionist state measures that often fostered the market for entrepreneurialism to expand and compound.

Quote from the book: “The three salient features of Meiji industrialization are very strong private sector initiative supported by appropriate official assistance, successful import substitution in the cotton industry, and parallel development of the modern sector and the indigenous sector.”

14. Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War by Bray Hammond

This next book covers a large extent of early American history from the 1770s to the 1870s but takes a keen interest in banking and monetary dynamics. Bray Hammond will provide the reader with an in-depth understanding of American economic history and its esotericisms. Hammond’s greatest contribution is the debunking of the myth of Andrew Jackson as a populist. Hammond argued that Jackson was an agent of private banking interests and much of his fight against the emergence of a central bank in America was to maintain the oligarchy of these private banking elites. They feared a “nationalist” central bank supported by the likes of Nicholas Biddle. The conventional narrative of this episode argues that the central bankers were the corrupt elites trying to harm the common folk. However, after reading Hammond, we can better see it was very much the opposite. The nationalist central bank would have been a much greater benefit to the common folk than the oligarchic banking system that Jackson tried to maintain. While a specific case study, this can teach about the fundamentals of monetary policy and how to deal with existing and regressive economic institutions.

Quote from the book: “This conflict of farmer and entrepreneur for dominance over American culture provoked much of the basic political controversy of the period from the Revolution to the Civil War…one has to discuss the function of banks.”

15. Sins of the Father by Conor McCabe

Conor McCabe wrote a fantastic economic history of modern Ireland. He explored older historical forces as well but crucially examined the ways in which a newly independent Ireland did not effectively rectify the imperial legacies that plagued it for so long. McCabe’s critique covered industry, housing, banking, farming, and more. In its encompassing expose, it pin points the exact ways in which Ireland would have better developed if another decision was made. Readers can use this specific diagnosis to bolster their general understanding. The critique of Ireland’s lack of sovereign central banking, proves the case for the need of sovereign central banking for example.

Quote from the book: “The most striking aspect of Fianna Fáil’s economic policy, though, was not that the Free State had finally caught up with the rest of the world and was using tariffs to protect and encourage domestic industry, but that, having committed itself to tackling the structural deficiencies in the Irish economy via tariffs, it then decided to fight with one fiscal arm tied behind its back. There was no move to create an independent Irish currency, no move to establish a central bank, and no move to break the crippling parity with sterling.”

16. The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea by Byung-Kook Kim, Ezra F. Vogel

South Korea is often used as a meme in contrast to North Korea. The free market South Korea vs. the socialist North Korea. However, this is a very dubious myth to promote. In reality, South Korea didn’t develop using traditional free market dogma. South Korea developed largely thanks to the visionary leadership of Park Chung Hee and his protectionist policies. Kim and Vogel provided an examination of Park and his role in the development of South Korea. They illustrate the undeniable role his protectionism played in growing South Korea. They also provide a fair portrayal of some of his more authoritarian aspects but this should be taken with the proper context of the place and time. We could easily call George Washington an undemocratic authoritarian tyrant for his persecution of common men during Shay’s and Whiskey rebellions or the obvious maintenance of the slave system. Yet, we usually never apply that standard to him and so we should not be too quick to paint with an overly broad brush upon Park. The reader should take away the idea that South Korea is an amazing country that grew rapidly after the terrible period of colonization and war. Any one criticism must be considered in the shadow of the hypergrowth and advancement that Park achieved. While the authors voiced a heterodox critique of Park at times, they provided a proper review of the existing literature on South Korean development. In some ways, their critique provided more substantiation of the efficacy of Park’s leadership than orthodox development economists would offer. The bottom-line is that the method in which South Korea grew was clearly inspired by the protectionist school of thought that has been outlined in this reading list.

Quote from the book: “The history of industrial policy under Park…was ‘unrealistic…a dangerous gamble, if not wishful thinking,’ to quote Nae-Young Lee. Likewise, Sang-young Rhyu and Seok-jin Lew’s Chapter 11 describes the consistently negative reactions of international donors and lenders, from U.S. policymakers to World Bank economists…to Park Chung Hee’s proposal to build an integrated steel mill.”

Additional Quote from Korea Times in 2010: “Korea at present has established the status of a global leader in the field of iron and steel making. POSCO has become one of the most efficient plants in the world, and has also become the first to introduce FINEX production technology, which is based on direct use of ore fines and non-coking coal to meet environmental standards ahead of global competitors to ensure a sustainable growth in the green steel industry.”

Amazing what not listening to western neoliberal economists can achieve!

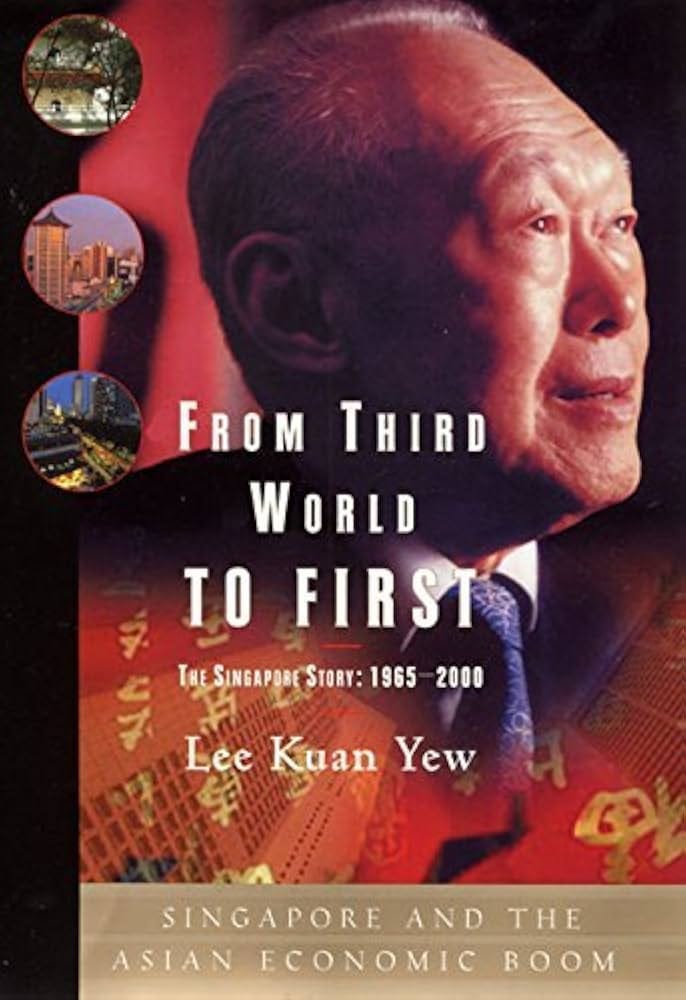

17. From Third World To First The Singapore Story 1965 to 2000 by Lee Kuan Yew

The final case study and book in this overall reading list is Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew’s account of his development of Singapore. He wrote this book as a manual in some regards for other leaders to consider. Through his account of his own trials and tribulations, he manifests one part general methodology and another particular style perhaps only suited to Singapore. It reminds the reader that while general theory is something we all lean on, we can’t lose sight that every society requires a unique approach optimized to its own place, time, and constraints. While Lee is often associated with the hyper-market economists, he in reality was much more protectionist than they would have you believe. He employed many policies that readers of this list would be familiar with — state-led industrialization being a critical one. Additionally, the personalization of economics and its political nature in the character of Lee is a healthy reminder. Too often do we get lost in the abstractions of economics and feel too comfortable in making sweeping assertions. In reality, the application of these economic ideas is a messy business of statecraft intersecting with the human condition. For example, Lee was constantly under the threat of conflict with the larger Malaysia and had to develop Singapore by any means necessary to offset that potential conflict. Another dramatic lesson to consider is that while Lee often appears as a technocrat far from these messy realities, he himself was almost killed as a young man during Japanese occupation during a massacre. Lee is a man that intimately understood these realities and that shaped his outlook on governance and the economics he employed. He is a much greater model of the full stack economist than any limp-wristed soft-handed economist you mind find in a western university. Perhaps that sentiment is best exemplified in Lee’s statement that “whoever governs Singapore must have that iron in him. Or give it up. This is not a game of cards! This is your life and mine! I've spent a whole lifetime building this and as long as I'm in charge, nobody is going to knock it down.”

Quote from the book: “We had a real-life problem to solve and could not afford to be conscribed by any theory or dogma…[the Development Bank of Singapore] helped finance our entrepreneurs who needed venture capital because our established banks had no experience outside trade financing and were too conservative and reluctant to lend to would-be manufacturers…Our job was to plan the broad economic objectives and the target periods within which to achieve them. We reviewed these plans regularly and adjusted them as new realities changed the outlook…We left most of the picking of winners to the MNCs that brought them...A few, such as ship-repairing, oil refining and petro-chemicals, and banking and finance, were picked by the [govt ministers]...or myself personally…Our ministry of trade and industry believed there could be breakthroughs in biotechnology, computer products, specialty chemicals, and telecommunication equipment and services...we spread our bets…We did not have a group of readymade entrepreneurs such as...industrialists and bankers...Had we waited for our traders to learn to be industrialists we would have starved…The government took the lead by starting new industries.”